Stories

Will the world ever emerge from its debt trap?

Profs. Jordi Gual and Pedro Videla look at the public-sector cost of COVID-19

COVID-19 has left many governments facing debt burdens not seen in peacetime eras.

April 30, 2021

Will governments around the world ever recover from the staggering amount of debt they’ve issued over the past year to battle COVID-19?

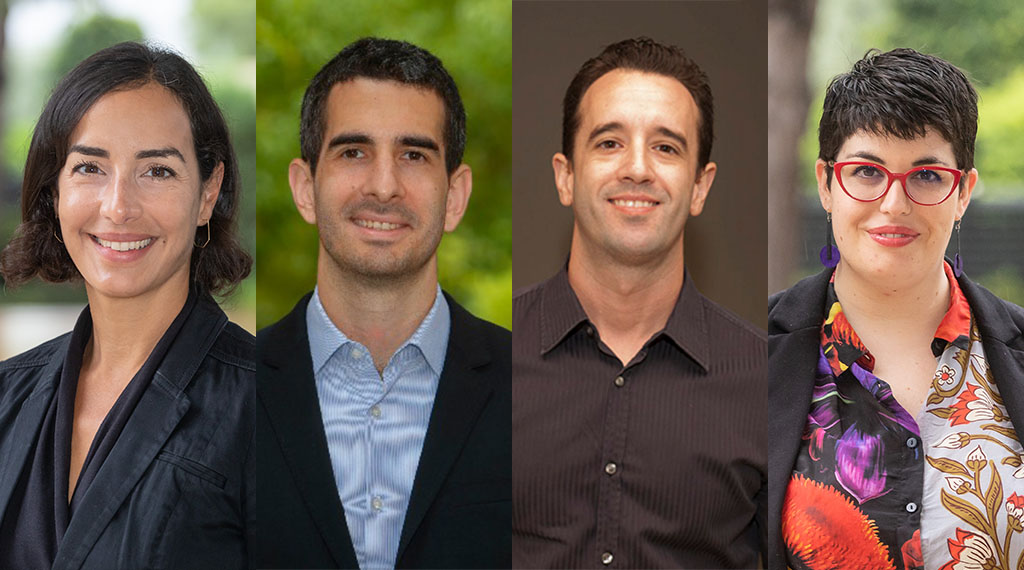

Professors Jordi Gual and Pedro Videla, speaking in an Alumni Learning Program session, offered a stark portrait of global public-sector debt. “We have never seen anything like this in a peacetime era,” Videla said. “We are facing humongous debt.”

Even before COVID-19, public-sector debt had been on the rise in many countries. Starting at least since the 1980s – through the ups and downs of economic cycles, and then spiking during the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08 – governments have generally spent more than they bring in.

But this 40-year-long debt spree culminated in COVID-19. When the pandemic hit, governments began debt-financed spending to fight the illness and keep economies afloat – at the same time growth plummeted. That sent debt-to-gross domestic product ratios through the ceiling – on average to 120% in developed countries — where they still remain.

So will the post-vaccination growth surge that many countries are hoping for be enough to revert the situation? “The higher the level of debt that you have, the harder it is to think that you’ll be able to get out of debt with growth,” said Gual, who recently rejoined the IESE faculty after serving as chairman of Spanish financial services group CaixaBank.

Adding an additional layer of concern is the fact that the main buyers of the debt over the past year are the world’s central banks, effectively increasing the money supply and keeping interest rates unusually low and even negative.

Lessons from the past, tools for the future

Gual looked at some of the tools and policies that have been used in the past to manage debt, including: economic growth; primary budget surplus; moderate inflation; financial repression (government policies that cap interest rates); restructuring and default; or a combination of a number of them.

Even if those have been used in the past, Gual noted, it’s unclear whether they will be used in the present or future. Super-charged growth is difficult in countries with large debts to service. Budget surpluses require austerity, which is highly unpopular socially and politically — and may also undermine growth. Domestic inflation wouldn’t help countries with portions of their debt in foreign currencies, and inflation behavior has confounded economists for 20 years. And financial repression is tough in countries with full capital mobility.

Restructuring and default can’t be ruled out – though it’s hardly the recipe for long-term economic health. “This sounds a bit surprising but it happened in the past, it happened in Greece, and it may happen in the future,” said Gual.

That means any solution will likely involve a battery of measures – plus, almost inevitably, higher taxes, both Videla and Gual said. But regardless of the complexity of the task, governments must make reducing the debt one of their priorities going forward.

Is it possible for governments to get out of the debt trap? “We must,” Gual said.