IESE Insight

A strategic approach to sustainability

Sustainability is now an imperative for business leaders seeking to prepare their companies for the future. Here's why and how you should incorporate environmental and social sustainability into your strategy.

As evidence mounts of the climate-altering toll human activity is taking on the natural world, sustainability has become a vital strategic consideration for companies around the globe.

The world is at a tipping point. Catastrophic weather events are more frequent and more prolongued. A generation of young people is demanding solutions to the planet’s problems. And the financial community has also awakened to the reality that climate and other sustainability-related issues will have real impact on their businesses.

But many companies struggle to come to terms with what sustainability means for them and for their strategy and operations. This article explores how senior managers might choose to address the challenge of environmental and social sustainability, not just for the sake of it being a moral imperative, but to perform their fiduciary responsibilities and to prepare their companies for the future.

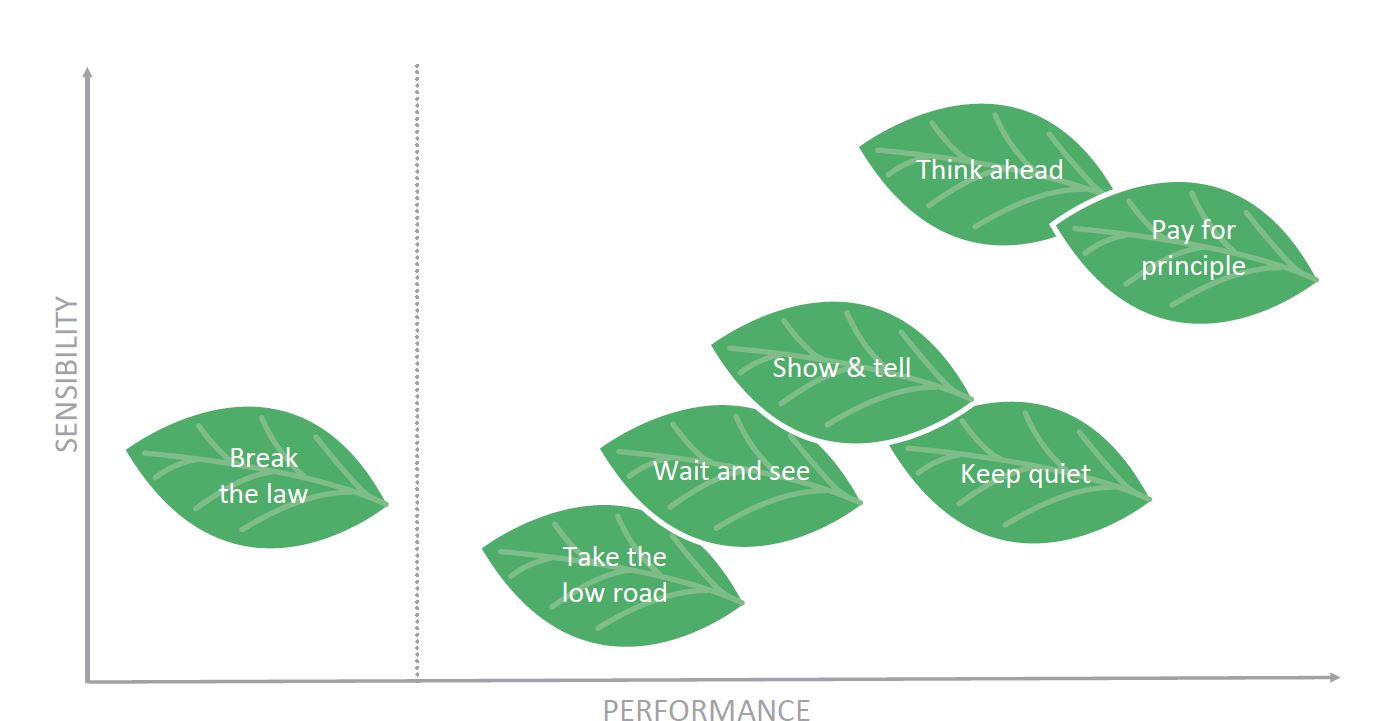

A word of warning: the path toward better sustainability performance is likely to be an arduous one for many companies. But while there are no easy solutions, in my years of teaching, researching, writing and consulting on this topic, I have seen seven strategic options that companies have chosen (six of them reasonable options and one which I do not recommend). I also offer a step-by-step approach for choosing the right path.

Different ways of seeing the world

To begin, we must understand why the business community has been relatively slow to embrace sustainability as an imperative. Part of the reason for this is the way sustainability concerns have been presented to most businesses, which fails to take account of the distinct way that many senior managers see the world. Their standpoints on the following issues need to be fully appreciated before any headway can be made.

The nature of business in society. Many environmentalists see the relentless drive for business profits as exacting heavy social and environmental costs. Business leaders, on the other hand, find this view misguided. Most businesses do not regard themselves as being anything other than forces for good in the world, attributing the advances and accomplishments of modern society to the hard work of entrepreneurs and the indispensable products and services they create for the world to enjoy.

The logic of business. Businesses tend to think in terms of three to five years. This is due to a variety of factors, including the time value of money, shareholder pressures, strategic planning cycles and the time-constrained career paths of most managers.

In contrast, most environmentally conscious stakeholders think in terms of decades, a time frame that is far beyond the scope, planning cycle or even the imagination of many business leaders, especially those running public companies.

Different priorities. The primary concern of many senior managers and board members is the financial performance of the firm. As such, environmental or social problems may not be viewed as a priority or they may arise as an unintended consequence of a firm’s cost-saving measures.

This focus on financial performance may contrast starkly — and sometimes directly — with a focus on long-term sustainability.

Just another business risk? When industrial accidents occur, business leaders sometimes appear genuinely surprised by the strength of feeling they generate.

Such was the case following BP’s Deepwater Horizon accident in the Gulf of Mexico. This is partly because, especially for those working in extractive industries, accidents like this are an assumed risk.

Victims of environmental disasters could not view things more differently. For them, such incidents are almost always avoidable and usually the result of corporate malfeasance and/or criminal negligence.

The limits of responsibility. Business leaders generally look to the government to set the rules of the game. So when they are held to much higher standards by the general public or an activist community, they cry foul.

Everyone desires clear ground rules by which to operate. The idea that a firm should be held liable for actions taken years ago when those same actions were legal is broadly seen as unfair.

Raison d’être. Business leaders can have a hard time understanding people who question the raison d’être of the company they work for. This is especially true of entrepreneurs who have spent their lives building a company from the ground up. Any rejection of the firm is perceived as a rejection of themselves.

Taken together, these differences help explain why business communities and environmental movements struggle to see eye to eye. While recent years have seen a coming together of both perspectives, there is still much work to be done by boards of directors and senior management alike, particularly in confronting strategic challenges in the environmental and social arenas.

Strategic challenges for business

Despite these differences, making the link between business and sustainability is crucial — not just for operational issues related to the day-to-day running of the firm, but for strategic issues that have a material impact on one or all of the following:

- the medium- and long-term viability of the firm.

- the financial performance of the business and shareholder returns.

- the size and scope of the business in terms of geographies and market segments.

Bearing in mind these make-or-break stakes, I identify the following reasons to justify making sustainability part of boardroom and C-suite strategy-setting processes.

The legal and social license to operate. While the legal ramifications of corporate environmental responsibility can generally be handled by a firm’s technical and legal staff, the social side is much trickier. A social license to operate is an indication of civil society’s acceptance or approval of a business or project, and is built on trust.

Events such as emission frauds by automakers rupture that trust between a firm and its consumers, or between a firm and its own employees. When the worst happens, the license to operate, whether legal or social, can be revoked.

The management of catastrophic risks. While risk management is a normal part of doing business, a full-blown crisis is usually unexpected and entails risks far beyond those that are normally discussed, planned and accounted for in financial projections. If a crisis has the potential to put a company out of business, it needs to be considered in a whole separate category.

Considering such risks, or even acknowledging their potential to occur, is difficult for senior management and runs counter to the quantitative approach to risk management with which executives will be most familiar.

Consumer behavior. Some customer segments, especially among younger generations, may abandon certain brands based on their (perceived) environmental or social performance. This is an area that, at the very least, merits tracking.

While it has become fashionable for marketing departments to attach the sustainability label to a whole gamut of products and services, what has not been demonstrated in any category besides food is the existence of a sizable market segment consistently willing to pay more for products and services that are perceived to be more environmentally sustainable. At least, not yet.

Given the growing allure of environmentally friendly consumer products, the biggest strategic risk that companies face is falling into the temptation of greenwashing their environmental performance. If companies make inaccurate environmental claims about their products or services, they run a very serious risk of being caught and called out for misleading customers. The damage of that can be irreparable.

The interplay between technological innovation and the environment. Our understanding of human health and ecology is advancing over time. What has happened any number of times is that products and practices which were thought to be safe have later proven to be harmful to people or the natural environment. A good example is phosphate-based detergents which came onto the scene in the 1940s and 1950s. It was only in the late 1960s that phosphates were found to cause damage to rivers and lakes and were eventually banned. Another more recent example is BPA, an additive to plastics that may be harmful to infants.

Returning to liability, the change for firms is the need to track science and technology to ensure their products and services are safe both today and tomorrow.

The environmental implications of globalization. Regardless of whether a firm operates in two, 10 or 100 countries, it must evaluate which environmental and social regulations pertain to it.

The choice is whether to follow the most demanding regulations across all markets, in which case a company might become uncompetitive in certain markets, or to adjust its policies to comply with the law in each country or territory, in which case it may run the risk of being accused of corporate hypocrisy or ecological dumping.

Assessing your environmental and social sensibility

Before deciding which strategic actions to take, a company needs to assess its current level of environmental and social sensibility in relation to the particular business it is in, the market(s) it serves, and the composition of its board, management team and shareholders.

Sensibility is the degree to which the people directly or indirectly involved in a firm’s operations are concerned about environmental and social sustainability. These people include shareholders and members of the board, the senior management team, line managers, employees and customers as well as government regulators.

Collectively or individually, consciously or unconsciously, these stakeholders will drive the firm’s sustainability agenda.

Several factors combine to produce varying degrees of sensibility. The purpose of the exercise is not to say that more or less is better or worse, but to check the current state of the company’s sensibility to sustainability issues both within and beyond its walls.

The following factors are worth considering:

The nature of the business and its regulatory burden. The first factor to consider is the nature of the business itself. Obviously, environmental issues are of much greater concern to a firm in the energy or extraction business than, say, a movie theater.

One could argue that all firms affect and are affected by the natural environment and need to think about their social impact. While this is certainly true, the environmental impact of a movie theater is significantly less than the impact of a strip mine or power plant, even if the theater is based in Miami and uses an inordinate amount of power for air conditioning.

Regulations vary enormously depending on the business you are in. There are also huge differences between environmental regulations and enforcement practices in different parts of the world. Companies that have to comply with tough laws and regulations will logically have a higher degree of sensibility than those that do not.

The commitment level of shareholders to sustainability issues. Another factor that can have an enormous impact on a firm’s level of sensibility is the degree of commitment of its shareholders.

Some firms have individual shareholders or shareholder groups that are deeply committed to sustainability, such as the Henkel family, Virgin Group’s Richard Branson and Patagonia’s Yvon Chouinard. In companies where such shareholders wield a lot of influence, the senior management will, as a matter of course, focus a great deal of attention on environmental and social issues.

Outside pressure from interest groups, customers, consumers and regulators. Outside pressure can also serve to heighten a firm’s sensibility. The constant spotlight provided by special interest groups and the news media can, at the very least, force senior management to answer for their company’s misdeeds.

This happened to Nestlé when it was caught using a palm oil supplier accused of unsustainable logging practices in Indonesia. As was revealed, despite being a member of the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil, the company did not have complete oversight of its supply chain. When Greenpeace produced a spoof Kit Kat commercial to draw attention to the company’s hypocrisy, it caused not only embarrassment but harm to the brand’s reputation.

In order to preempt such scandals, more and more retailers and manufacturers are asking for detailed information about the environmental impact of their suppliers’ manufacturing processes. In many industries, it is now necessary by law to go all the way back through the supply chain to ensure there is nothing untoward.

Internal interest, primarily among key segments of the firm’s employees and managers. Such pressures are also increasingly influencing internal procurement policies, especially among firms that are acutely susceptible to reputational damage.

Google, Apple and Meta, for example, are carbon neutral and continue to reduce the carbon footprints of their giant server farms. In my view the main reason for this is to be able to attract and retain talented people in their 20s and 30s.

Weighing the strategic options

Once your current level of sensibility has been assessed, the next step is to determine how much to do along all of the different aspects of environmental and social sustainability, assuming that the baseline is what is required by law.

To be clear: I do not recommend the option of non-compliance, or the strategy I call “break the law.” I discuss it because we have seen a number of companies follow it.

1. Take the low road

This strategy would consist of doing the absolute minimum required to comply with the laws in each of the countries and territories in which your company operates. This implies taking a reactive stance to changes in legislation, societal norms or new industry developments.

While there is nothing wrong with this approach from a legal standpoint, one might question its wisdom from a dynamic perspective since, over time, laws and regulations will inevitably change. Adapting late to evolving trends may be more costly than being an early mover. An even greater danger is that if senior management sends the message that minimal compliance is sufficient, employees may interpret this as tacit approval to cross the line — as long as they don't get caught.

2. Break the law

The option of deliberately choosing not to comply with certain legal norms is not to be recommended or endorsed. Aside from ethical considerations, the approach can pose a serious risk in terms of potential loss of your legal and social license to operate, and can even land you in jail.

Ironically, to break the law, you have to expend a lot of effort on understanding all regulations in the first place, in order to find ways to exploit loopholes and creatively avoid compliance. It would seem to make more sense to channel all that valuable environmental and social sensibility you will have acquired in positive directions.

3. Wait and see

The approach that may make sense for some companies is to comply with the basic legal requirements in force today and also to actively monitor the changing values of employees, consumers and society, and to track potential legislation.

This approach requires a somewhat higher degree of sensibility than, for example, Take the Low Road, as it will make sense to begin gathering data on the firm’s current environmental and social performance in order to be prepared for the future.

4. Show and tell

This strategy involves making important progress on sustainability and then making it a key part of the firm’s communications strategy. Show and Tell should not be confused with greenwashing, which is about showcasing the few sustainable activities a company has to give a false impression. On the contrary, Show and Tell is about putting a positive spin on an authentic and compelling story.

The danger with Show and Tell is that if sustainability is central to communications, the firm must have a similar level of commitment in all of its activities and in all countries and territories. Evidence of a double standard between a firm’s environmental practices in developed and developing countries can, for example, be used to challenge a firm’s social license to operate.

A related issue is what Helle Bank Jorgenson, founder and CEO of Competent Boards, calls "greenwishing," which is about making bold claims for the future without having detailed plans or initiatives to bring them to fruition.

5. Keep quiet

An interesting counterpoint to Show and Tell is what I call Keep Quiet. There are a number of companies that do meaningful work on the environmental and social sides of sustainability but that do not, for a variety of reasons, make it the center piece of their communications. Such companies will publish sustainability reports and participate in initiatives such as the Carbon Disclosure Project or Science Based Targets but keep a relatively low public profile.

What I have seen recently is that some companies, such as German chemical and consumer goods company Henkel, have chosen to move from Keep Quiet to more of a Show and Tell stance. Henkel has been a leader in environmental issues for decades but only recently has begun making its commitments and activities better known.

6. Pay for principle

This option is for those companies in which leadership chooses to take the firm in a sustainable direction based on their own ethical convictions.

In this case, the fundamental rationale is not a medium-term business case but rather a deep belief that reducing air and water pollution, protecting the natural landscape, becoming carbon neutral or making progress on a whole range of social issues are critically important tasks and should form part of the corporate agenda.

An early pioneer of this approach was the late Ray Anderson, the founder and chairman of Interface Inc., one of the world’s largest manufacturers of modular carpets. After reading Paul Hawken’s The Ecology of Commerce in preparation for a speech on his company’s environmental vision, Anderson realized that for Interface to become 100% environmentally neutral, it needed a complete overhaul of the way it operated.

Within a year, it had reduced average consumption of fiber by 10% per square yard. Four years later, it introduced a carpet tile product made with 100% recycled nylon face fiber and a layer of 100% recycled vinyl material in the backing.

7. Think ahead

The final approach requires going beyond what’s needed today. Based on hard business logic, the senior management team accepts that the world is changing in specific ways.

To build competitive advantage, to hedge against future legislation and to tackle emerging strategic challenges, the firm believes it is better to be at the leading edge of the sustainability movement rather than trailing behind.

That means starting now, because radically reconfiguring a corporate culture, mindset and environmental footprint takes time and energy, especially for large organizations which might have dozens of operating units, hundreds of stores, or, in the case of a company I know well, thousands of trucks.

Think Ahead is the opposite of greenwishing. In Think Ahead, the company has a detailed plan over the next five to 15 years to transform its operations into a more sustainable model.

Choosing the right path

Trying to decide which of the previous strategies is most appropriate for your own firm is not easy. Each of the strategic options presents an array of potential risks, trade-offs and opportunities. Moreover, there is no telling what will happen in the next five, 10 or 20 years.

To help improve your chances of choosing the right path, I suggest you follow these steps:

1. Take a long, hard look back

A company’s options — in the environmental and social arenas as with just about everything else — are largely conditioned by its past. Academics call this “path dependency.” Put simply, you are where you are today because of where you have been, and your next steps are partly conditioned by your last ones.

The idea is to look at the evolution of these issues in the past. I suggest doing that across four different aspects: across the industry as a whole, across the specific regions where you are doing business, across the positions of environmental interest groups and, finally, across your company itself.

How has your firm dealt with these issues in the past? Has it always been a leader, giving it a rich legacy to draw on? Or have these issues largely been ignored — or even worse — in the past?

Engaging in a process of in-depth self-reflection can be painful for an organization, even if the executives responsible for past crises are no longer in place today. Those events can, however, leave a lasting impression on people, both inside and outside the company, and can condition its future responses.

As such, the first step in developing a strategic approach to sustainability is to honestly assess how the firm has behaved in the past.

2. Understand the present

After analyzing the past, the next step is to understand the present across the same four dimensions (industry, region, interest groups, company). This means exploring, in as much detail as possible, the firm’s current position vis-à-vis its competitors, its relevant regulations and its relationship with stakeholders.

A business acquires its strengths by developing winning strategies, and by having the right people and processes in place to make those strategies work. Nurturing your strengths requires time, investment and managerial attention, so understanding the present is critical in determining what level of effort is required next.

For firms producing sustainability reports according to the guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the current situation should already be well documented.

3. Look to the future

Once the past and present are well understood, it is time to look ahead and explore what the future might hold. This involves analyzing different potential scenarios for the various regions and territories in which the firm operates.

Posing alternative scenarios is preferable to making forecasts, since anticipating future levels of environmental and social commitment among the general public, interest groups and regulators with any degree of accuracy is an almost impossible task.

4. Bring it all together

The analyses of the past, present and future should then be compiled into a single framework. This helps to synthesize the sustainability issues not just at the firm level but across regions, industries and stakeholder groups, including customers and suppliers.

For companies involved in many different industries and regions, separate analyses will need to be conducted for each.

Finding a common strategy that applies universally across all of a firm’s business units is unlikely. As such, it may be necessary to let certain units take different paths, and depict them separately.

5. Bring the board on board

At the operational level, sustainability will typically pay off within a reasonable timeframe; thus, the CEO can trust the different directors or vice presidents to make the business case to replace ageing infrastructure or to invest in social programs.

What may be harder to do is to make the case for the strategic issues mentioned above. For that reason, it is essential to involve the Board of Directors, or whatever governance body the firm has, in choosing the overall strategic approach.

For example, adopting a strategy of Think Ahead, based on an understanding that tomorrow will be different from today, is a leap of faith that must be made from the top.

6. Communicate and train

Once the strategy is clear at the top, the success or failure of many strategic environmental and social initiatives depends on the quality of the training and support that managers, employees and other stakeholders receive.

Some people might say that every firm should do all it can across all aspects of sustainability. I disagree with this approach. Each firm needs to determine those aspects that are most material or important to its own strategy and to its key stakeholders.

Once that is done, I believe that the most effective way to get everyone on board is to craft a clear strategic vision that is easy to communicate. For example, if the message is that the company will be a leader in its market segments and in the countries where it operates on a certain set of issues, senior management can give space to the relevant parts of the organization to figure out what that means and how to get there.

Framing sustainability in these strategic terms is, I believe, much more likely to convince the entire organization to buy into the issue. And your company, not to mention the planet, will benefit.

This article is partly based on the book Strategy and Sustainability: A Hardnosed and Clear-eyed Approach to Environmental Sustainability for Business by Mike Rosenberg (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

A version of this article was originally published in IESE Insight magazine (Issue 29, Q2 2016).