IESE Insight

The creative odyssey of Stanley Kubrick

We revisit Stanley Kubrick's groundbreaking classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey, to discover some keys to innovation from the filmmaker's creative process.

When the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey hit theaters in April 1968, few could imagine just how accurately its director, Stanley Kubrick, had divined the future. Indeed, many moviegoers were nonplussed, with one New York Times critic remarking, "The movie is so completely absorbed in its own problems, its use of color and space, its fanatical devotion to science-fiction detail, that it is somewhere between hypnotic and immensely boring. The uncompromising slowness of the movie makes it hard to sit through without talking — and people on all sides when I saw it were talking almost throughout the film."

And yet, more than half a century later, the movie's vision of a man at odds with his computer and its depiction of future technologies — voice assistants, artificial intelligence, touchscreens and robotic arms — are hailed for being a prescient masterpiece.

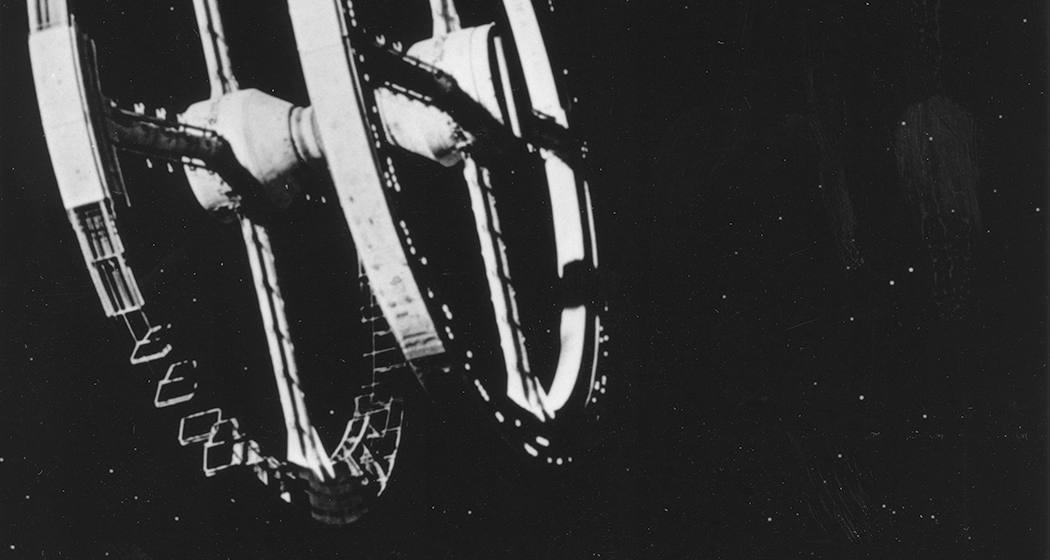

Kubrick's innovations are the subject of a touring exhibition. Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition provides clues as to how one might go about imagining the unimaginable, like he did, "from predicting the modern tablet to defining the aesthetic of space exploration a year before the moon landing," in the words of the exhibition.

Imagining the future

It all starts with collaboration. Kubrick teamed up with the legendary sci-fi writer Arthur C. Clarke, whose story, "The Sentinel," provided the initial inspiration. The two wrote the screenplay together. They wanted to tell a good story but they also wanted it to be epic ("Go big or go home!" you might say today). They tackled such weighty themes as human evolution, alien life forms and our place in the universe. But it was the special visual effects — for which the movie won an Oscar — that stand out most to this day.

When it comes to fear of robots taking control and replacing human workers, Kubrick certainly got that part of the 21st century right. How did he manage to come so close to the mark when aiming to capture the future?

It helps that the movie was set in 2001 — a near future rather than a distant one. The farther you stray from the present, the more you must rely on guesswork, and the more fanciful your predictions become. Kubrick, however, wanted "a believable future," as the director of London's Design Museum told CNN, not of "bug-eyed monsters" but with "plausible spaceships." Kubrick insisted on his future being grounded in proximate realities, based on data and supported by scientific experts, so that it fell within the realms of possibility.

Considering every angle

His obsession with accuracy and attention to detail drove him to take apart any object he was studying in order to understand not only its precise nature but its context and relationship to other concepts. This painstaking process of deconstruction and reconstruction enabled him to tease out new connections and meanings. (It also sometimes led to blockages, as with his Napoleon project, which never came to fruition because he spent so many years researching the details, including the legendary tale of him sending a production assistant to Waterloo to gather soil samples just to replicate the same earth on screen.)

His inquisitive mind led him to search out the leading lights in science and engineering, so they could advise him on technical aspects and ensure that his results were as realistic as possible. Despite his projects being shrouded in secrecy (even Clarke didn't see 2001 until it premiered), he frequently held meetings with outside experts to learn about the latest developments in a field and to put his own ideas to the test.

For example, he sought advice from no less than the U.S. space agency, NASA, for building his own movie spacecraft. A British aerospace company built the giant, rotating centrifuge set the size of a Ferris wheel. And the renowned scientist Marvin Minsky provided input on the pioneering field of artificial intelligence. (One of the movie's characters, Dr. Kaminsky, was reportedly named in Minsky's honor.)

Kubrick would explore a given scenario from almost every possible angle: geopolitical, economic, social, technological. For 2001, he analyzed what was going on in the world, then imagined how it might evolve and reflected that in the movie.

So, while the Space Race was at its height in the 1960s, he figured the Cold War would thaw eventually, and his movie's vision of an international crew working together in a space station has, as we know, become the norm.

Now, as the world braces itself for corporate-sponsored space tourism and human missions to Mars (the planet before Jupiter, the destination of 2001's space voyagers), what kinds of credible scenarios could we likewise project 50 years into the future?

Pragmatic creativity

Although famous for elevating his craft to an art form, Kubrick couldn't completely ignore commercial considerations. He may have eschewed cranking out Hollywood blockbusters, but he knew he had to achieve a certain degree of financial success in order to continue indulging his passion projects. Some say he was uniquely able to do both.

"You are always pitting time and resources against quality and ideas," he said in an interview, likening filmmaking to a game of chess.

Chess also taught him to approach things in a more strategic, disciplined way: "Among a great many other things that chess teaches you is to control the initial excitement you feel when you see something that looks good. It trains you to think before grabbing, and to think just as objectively when you're in trouble. When you're making a film ... a few seconds' thought can often prevent a serious mistake being made about something that looks good at first glance."

This is not to say that he didn't allow room for spontaneity within that careful, meticulously thought-out approach. The script, for him, was a starting point, the foundation of the overall plan. But it was never beyond revision — it was also a jumping-off point. For all the prior planning that goes into a project, you never really know what innovative results will arise until you shout, "Action!"

Kubrickian: 4 plot points from a creative genius from IESE Business School

A version of this article is published in IESE Business School Insight 153.