IESE Insight

Collectivists or individuals? How relational mobility affects worldview

Is it easy to make new friends where you live and work? The answer to this question has implications for how you and your colleagues think — analytically or holistically — according to new research.

Do you make (or lose) friends easily, or do you have the same childhood friends for life?

How you answer this question may well point to the kind of culture you were raised in. And social scientists believe they can extrapolate still more information about you, such as whether you think holistically or analytically, and whether you tend to feel you control your environment or are at the mercy of it.

IESE professor Alvaro San Martin, with Joanna Schug and William W. Maddux, explores the relationship between relational mobility and thinking styles in a paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Where you come from says a lot about you

Relational mobility refers to the degree to which relationships in a society are fixed. This affects both stability and choice: in some cultures, individuals can choose friends and romantic partners and may change them at their convenience; whereas in other cultures, relationships tend to be long-lasting and stable but present few options for choice or change.

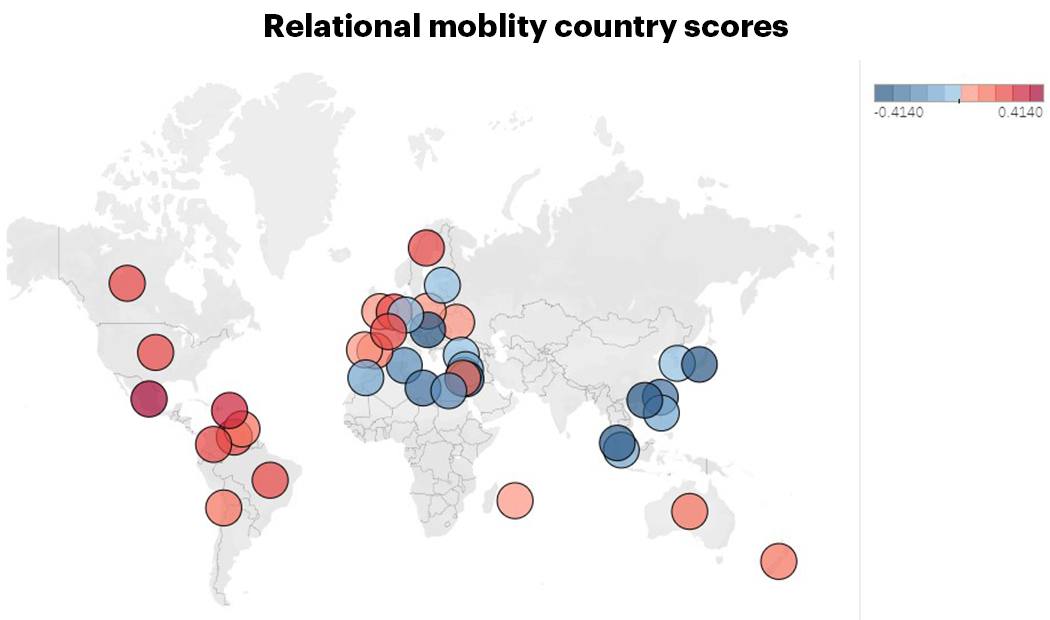

San Martin also coauthored an earlier, seminal study that measured relational mobility in 39 countries and found that it helped predict social behavior in these places. As might be expected, the study reported that Western Europe and the Americas featured higher levels of choice, while East and South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa had less fluidity. Drilling down, Portugal appeared as the study’s midpoint (0), with Mexico scoring highest and Japan lowest. See figure below.

Source: Thomson et al. (2018)

In examining why this might be, the authors looked at the role played by the cultures’ traditional forms of subsistence. Notably, where people once relied on something very stationary like rice farming (stable, long-term, centered through generations on the same land), relational mobility tends to be low. Where people relied on herding or hunting (individualistic and more migratory), relational mobility tends to be high.

It’s all in your head

San Martin and his co-authors consider how relational mobility may affect broader thought patterns. They theorize — and then demonstrate across six studies and experiments — that how we make and retain relationships causes us to see our world in particular ways.

In cultures in which a social circle is more or less fixed, people tend to be vigilant about what is happening in their environment. Any interaction, bad or good, is likely to have consequences when that person inevitably reappears. Such individuals are more likely to view the world holistically, “to see objects as overlapping and embedded in a continuous context.”

This affects not only their general worldview but also their interpretations of others’ actions: holistic thinkers see actions as grounded in a broader context.

That is not the case in cultures where relationships are less stable. When individuals are less concerned about the consequences of harming social connections, they also tend to be quicker to take responsibility for their actions (be they positive or negative). This leads to analytical thinking, a tendency to focus on distinct objects as isolated from each other, and a tendency to attribute others’ actions to their individual personalities, rather than influenced by outside factors beyond any one person’s control.

In a world with increasingly multicultural neighborhoods and workplaces, putting yourself in the shoes — or rather cultural context — of others, may be a first step toward overcoming cultural clashes and misunderstandings.