IESE Insight

Shutting the doors to foreign trade and investment? At what cost?

The annual ranking: Switzerland, Singapore and the United States are the world's most competitive countries. Meanwhile, openness to foreign trade and investment is in a 10-year decline.

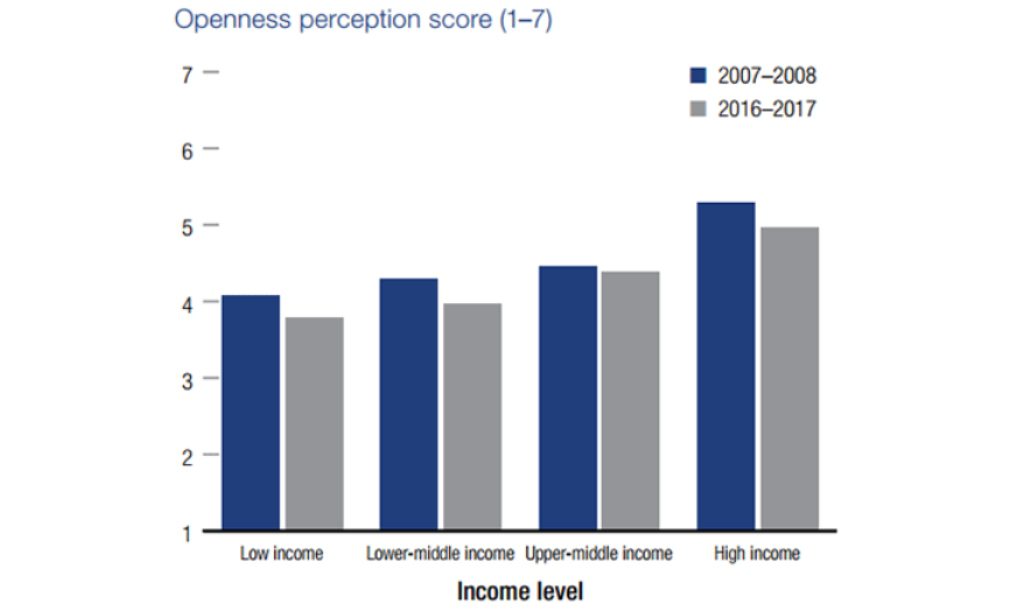

There's been a 10-year decline in the openness of economies around the world, at all stages of development, according to The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017. Published by the World Economic Forum (WEF), this report assesses the productivity and competitiveness in 138 economies each year.

Protectionist measures that reduce foreign trade are trending at all levels, but the report states that the effect "is most keenly felt in the high and upper middle income economies." And that analysis is based on data which does not yet reflect the Brexit vote of June 23, 2016.

Each year, the WEF also releases its famous ranking of the world's most competitive economies. For the eighth year in a row, Switzerland tops the charts, narrowly ahead of Singapore and the United States. The Netherlands and Germany follow in fourth and fifth place, respectively, with Germany climbing an impressive four places in two years.

Rankings are based on the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), in which competitiveness is defined as the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country. Professor Pascual Berrone and researcher María Luisa Blázquez of IESE's International Center for Competitiveness (ICC) serve as collaborating members for the WEF, covering Spain for the compilation of the report.

Where competitiveness and productivity lead to prosperity

Europe is the dominant region in the ranking overall, taking six of the top 10 spots. Sweden, the United Kingdom (with pre-Brexit data) and Finland sit at 6, 7, and 10, respectively.

Yet the north-south divide in Europe persists, with southern economies generally seeing lower index results. This year, Greece falls five places to 86, while Italy slips one spot to 44. In contrast, Spain delivers better news, as it climbs another rung to 32. Spain has climbed three spots in two years and stands out for its infrastructure, market size, technological readiness and business sophistication. Its weak points are its macroeconomic environment (burdened by heavy government debt) and its labor market efficiency (with restrictive labor laws).

In terms of the closely watched BRICS, China holds steady at 28 while India gains the most ground, jumping 16 places to 39. Russia and South Africa move up two spots to 43 and 47, respectively, while only Brazil stumbles: it falls six rungs to 81.

An alarming 10-year trend

The WEF's annual survey of executives' perceptions points to problems ahead for productivity. According to Klaus Schwab, the WEF's founder and executive chairman: "Declining openness in the global economy is harming competitiveness and making it harder for leaders to drive sustainable, inclusive growth."

Source: The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017, p 11

Openness to international trade in goods and services is "directly linked to both economic growth and a nation's innovative potential," the report states. Meanwhile, survey results point to a gradual closing of borders — mainly a rise in non-tariff barriers (e.g., added legal and normative requirements). That said, three other factors are in play: burdensome customs procedures, restrictive rules affecting foreign direct investment (FDI) and less foreign ownership.

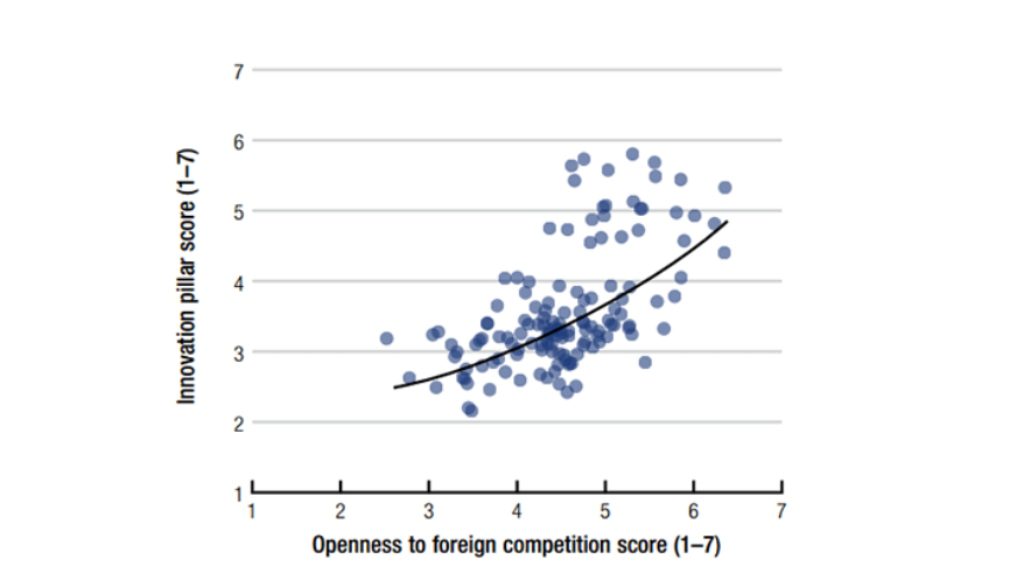

The WEF's report emphasizes that openness and innovation "go together and reinforce each other." In fact, the WEF reports a clear correlation between economies' openness to foreign competition and their scores on innovation.

Source: The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017, p 11

Methodology, very briefly

The WEF's Global Competitiveness Report has ranked economies based on its Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) since 2005. The 138 economies included this year represent 98 percent of the world's GDP.

GCI rankings are evaluated for each economy according to 12 pillars of competitiveness: institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labor market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication, and innovation. The 12 pillar scores are based on 114 indicators, which are assessed based on statistical data (from internationally recognized organizations) as well as perception data, which comes from the GCI's Executive Opinion Survey. This survey has become one of the largest executive studies of its kind, collecting the perceptions of over 14,000 business executives in the 138 economies.