IESE Insight

Preventing free-riding: how to run a tight multiparty alliance

To tackle a fundamental technological problem and innovate, it often makes sense to work together with other firms or organizations, be they private or public. But when many collaborate, preventing free-riding is an issue. IESE's Massimo Maoret looks at alliance free-riders and what levers might induce more effort.

"Two minds are better than one," the old saying goes. Cooperation and teamwork studies have shown the many benefits of putting multiple heads together to solve problems and facilitate learning. And a growing number of multiparty alliances — which may involve private firms, universities, research centers and/or government agencies — are designed to put this truism into practice.

Indeed, collaboration is considered so important a skill that most of us learned it early at school, in group projects. And a common memory from this time is of doing the work while another team member sat back and still reaped the reward.

It happens in school and it happens thereafter, as IESE's Massimo Maoret, with co-authors Fabio Fonti and Robert Whitbred, points out. "Free-riding" is one major drawback to cooperative working alliances between firms and other entities. The chance that committing to an alliance could encourage another member to free-ride, or reap benefits while under-contributing, can undermine both an alliance's effectiveness and its morale.

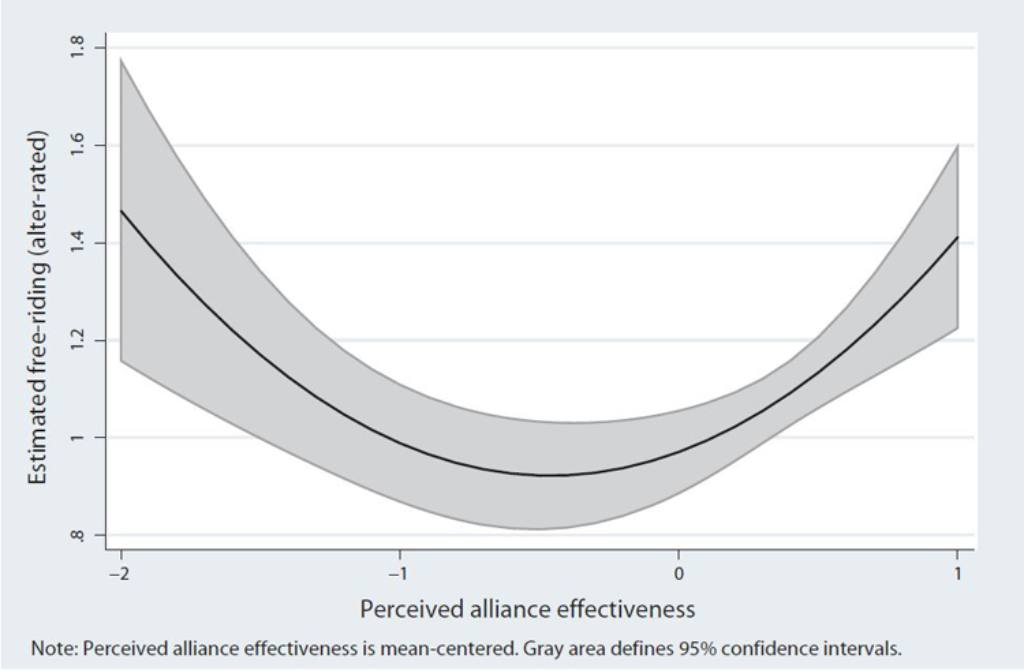

The authors delve into the factors that may dampen effort levels. Specifically, they look at a research consortium and find that perceptions of the effectiveness of this alliance play a strong role in determining commitment levels. Here, it turns out, free-riding is most prevalent when an alliance is deemed either very effective or barely effective at all. Middling expectations spur more effort.

What to Do About the "U"

Riding on the coattails of other partners' efforts has long been highlighted as a challenge to the alliance model, but most literature focuses on how to design an alliance effectively to prevent free-riding. Maoret and co-authors take a different tack, examining how and why free-riding develops when an alliance has already been formed.

Perceptions, which help determine effort levels, are often informed by how well the alliance is functioning. When an alliance is working particularly well and free-riding occurs, a manager might spur more effort by dampening rosy outlooks. Meanwhile, alliances that are not perceived as working well present a particular problem, as poor outcomes and free-riding can mutually reinforce one another. At such times, a manager might find it's time to disband an alliance before it gains downhill momentum.

It's also noteworthy that alliance participants seem to gauge how much they should commit to a joint project by looking over at organizations that are similar (i.e., other private firms or other universities in a diverse group).

The bottom line: By better understanding what leads to free-riding, alliance managers can work to encourage participants to commit more to joint efforts. Here, leveraging perceptions might be one of the few tools managers have to minimize free-riding — especially in alliances where profit or productivity incentives are low.

Methodology, Very Briefly

The co-authors analyzed primary data from a 40-member technology consortium comprised of universities, firms and government agencies aiming to innovate machine tool technology. Open-ended interviews with consortium members were conducted as well as structured 60-minute surveys. The co-authors also gathered evidence from two experimental designs, recruiting 879 participants via Amazon's Mechanical Turk.

Massimo Maoret's research activities were supported by the European Commission (Marie Curie Career Integration Grant FP7-PEOPLE-2013-CIG-631800).