IESE Insight

Discover how to use network effects to grow your platform business model

Platform business models need to look beyond quantity to get at the roots of what is providing value. As this new framework reveals, not all feedback loops are positive.

Platform-based business models create and facilitate exchanges between two or more interdependent parties, typically producers and consumers. Such business models have famously fueled the rise of Big Tech players like Amazon, Facebook and Google. Their value is predicated on having an online platform that acts as a conduit for connecting buyers with sellers (Amazon), users with other users (Facebook) and content providers with searchers (Google), where the platforms make money off the exchange and charge a premium for advertising.

A key facet of platform business models is their ability to generate so-called network effects. A traditional telephone network is the classic example of the network effect in action. When telephones were invented, network effects were nil because there had to be another phone on the receiving end in order for a call to have any value. But as more telephones got connected, a vast network was formed. The value of each call increased, not only for each new phone that joined the network, but also for those already in the network. The rest is history.

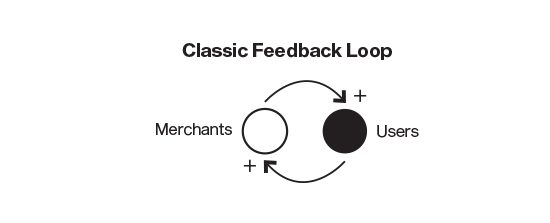

This same dynamic underpinned eBay’s success in the early days of the internet. The online marketplace was one of the first to offer itself as a platform for buyers and sellers to find each other and conduct transactions directly: the more sellers, the more buyers, and vice versa, feeding a positive feedback loop. This is how a double-sided platform works: eBay’s network just kept growing bigger and getting stronger, until it became a market leader.

What makes today’s network effects special is the amplifying effect of digital tech, which has turbocharged a business’s ability to grow a vast global network and lock participants into a platform on which their exchange depends. It’s what every tech startup aims to achieve, following in the successful paths trailblazed by Amazon, Facebook and Google.

The power of network effects is often attributed to an ever increasing quantity of actors. But this is only part of the story.

New research by IESE’s Llewellyn D.W. Thomas — published in Academy of Management Perspectives with co-authors Kimmo Karhu and Mikko Heiskala of Aalto University and Paavo Ritala of LUT University — finds that just getting more and more actors to participate in your platform business is no guarantee of generating the positive network effects that you desire.

Indeed, there could be unanticipated negative effects. The authors tease out the nuances in their paper, showing how the network dynamics play out differently for different types of platforms.

Think back to the earlier examples. In the telephone network, what each new user finds valuable is the identicality of the connection with other users. On eBay, by contrast, each seller who joins the network is selling a different thing: what counts for buyers is the variety of the offer.

So, yes, while quantity is still important for platform businesses, and yes, quantity remains the most intuitive way of thinking about network effects, the authors insist there are other features that make a platform valuable to users, not only to get them there but to ensure that they stay.

More vs. less, persistence vs. transience: the issues that make a difference

The research defines various types of platform interactions, summarized in the 2x2 matrix below. By charting the different types of platform exchanges, business practitioners can start to think more deeply about these phenomena, especially to understand and foresee potential competitive dynamics that could affect their own positioning, for better or for worse.

Consider Uber. On the one hand, a ride is a ride is a ride. Indeed, Uber goes to great lengths to make each ride similar, simply to move a user from point A to point B. In this sense, the platform is trying to maintain the identicality of the experience (that is, to keep “heterogeneity of value units” low) in order to attract, keep and grow users (drivers and riders) who wish to broker their exchanges via this business platform. This identicality is a key feature of the Quantity corner, and it is where the telephone network succeeds.

However, the reality of Uber is that the offer of rides comes and goes — not all drivers are available at any given moment. As such, “the persistence of value units” is also low. When value units are both transient and homogeneous, this is called Utility. In such case, the value does not accumulate so readily.

What if, like Uber, “persistence” is low but there is high “heterogeneity”? This would be eBay. The authors categorize this as Variety because there are a lot of different items being sold, and each is transient as new items are listed, sold and removed. App stores would also fall into this category. The more apps, videos and other content available for selection, the better.

The final camp is Accumulation. Here, there is high “heterogeneity” but also high “persistence.” Think Wikipedia, Reddit or Stack Exchange. There are millions of articles freely available, which are constantly being updated and enriched with new comments, hyperlinks and references, with each new piece of information adding value that keeps accumulating over time.

Identifying other types of feedback loops and externalities

The authors take their model further, wanting to show how the feedback loops of the previously described networks generate different types of externalities, sometimes negative as well as the positive ones that practitioners are most familiar with.

Going back to the eBay example, while the externality is variety-based, sellers are only really interested in the number of buyers on the platform. So, the network effect consists of both variety and quantity externalities interacting in a feedback loop. This poses interesting implications: does each externality create the same value and growth, or is the feedback loop misbalanced and a potential threat to growth?

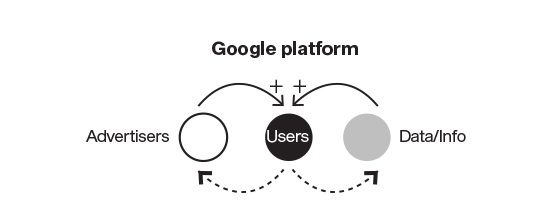

The authors identify various other types of feedback loops, apart from the most common one of two externalities reinforcing each other in a positive cycle of growth. Google, for example, with its reliance on both advertising and user data, illustrates what the authors label as a double cross-side interaction, where two externalities benefit the same actor, which in turn feeds user growth. The authors present several other models like this (e.g., balance effect, same-side boost, collateral effect, boomerang effect) to show the nuanced dynamics beyond the classic feedback loop. See the graphics below.

All this is to say that managers and architects of platform business models need to think beyond quantity in their analyses. This research highlights the importance of thinking more rigorously about the variety — or lack thereof — on a platform.

Also, more thought needs to be given to how transient the items on a platform are.

By unbundling network effects into four distinct types (as depicted in the 2x2 matrix) and identifying how externalities interact, the authors raise important implications for platform competition, governance and regulation.

An infographic of this article is published in IESE Business School Insight magazine #168 (Sept.-Dec. 2024).