IESE Insight

How K-culture conquered the world

From K-pop to K-dramas, industry insider Lee Areum discusses the global mania for all things Korean and why she thinks the best is yet to come.

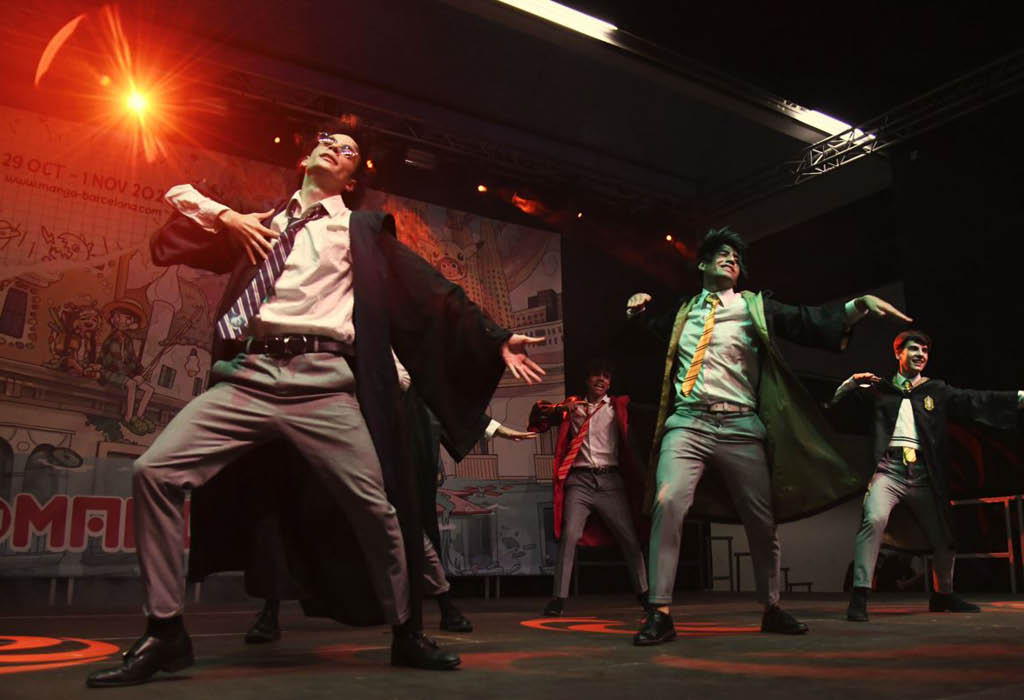

In December 2022, over 150,000 people attended Manga Barcelona, one of the biggest conventions of Japanese culture in Europe, which had to move to a larger site to accommodate the growing number of visitors attending the sold-out event. Young and old alike made their annual pilgrimage to this four-day fanfest, many dressed up as their favorite manga (comic book) or anime (animated TV or movie) characters (what’s known as cosplay, a portmanteau of “costume play”). Although inspired primarily by Japanese culture, there is crossover appeal with other Asian trends — notably the rise of Korean pop music or K-pop. On the final day, dozens of youth took to the Grand Stage for a K-pop dance competition called K-pop Assault: Wow, Dancetastic Baby 2022. Local troupes, after weeks of tryouts and practice, faced off before the judges for the chance to be crowned the queens and kings of K-pop choreography.

How is it that tens of thousands of Europeans are so enthralled by cultural curiosities that originate 10,000 kilometers away from them, as opposite (literally) as East is from West, and yet they feel as passionately about them as if they were their own?

There’s something about Asian aesthetics and culture that are universally appealing, says Meritxell Puig, director of Manga Barcelona. It may start with manga, but it’s a gateway to gastronomy, language, travel, literature and, of course, music, drama and dance. Understand it or not, the fascination is growing.

This is a triumph of “soft power” — exerting positive influence such that others admire your values and aspire to follow your example. According to the U.S. political scientist Joseph Nye who coined the term, culture is a key asset to soft power. Or as a former South Korean president put it, in the 21st century, culture is power.

Indeed, numerous indices chart the rise and fall of countries according to their soft-power advantage. Although Japanese pop culture maintains its global appeal (as evidenced by Manga Barcelona, now in its 28th edition), it is South Korea, in particular, that has been on the rise in recent years — reaching 2nd place in Monocle’s Soft Power Survey 2020.

Tellingly, when U.S. President Joe Biden made a statement denouncing hate crimes against Asian-Americans that have spiked since COVID-19, he did so alongside members of the K-pop boyband BTS who have famously enlisted their army of fans to take up social justice causes.

Peace and love: U.S. President Joe Biden and the K-pop group BTS make finger hearts in the Oval Office in May 2022. PHOTO: Adam Schultz/The White House

Peace and love: U.S. President Joe Biden and the K-pop group BTS make finger hearts in the Oval Office in May 2022. PHOTO: Adam Schultz/The White House

To delve into the Korean Wave — aka Hallyu — Jonathan Park, director of Corporate Partnership and Executive Education for IESE in Seoul, spoke with Lee Areum, a South Korean entertainment industry executive and co-author of the Music Business Bible.

With a background in economics, Lee got her start in the entertainment industry in 2002, the year that South Korea co-hosted the FIFA World Cup with Japan and reached the semifinals — a sign that the country was becoming a force to be reckoned with. She joined JYP, one of the Big Four agencies (alongside SM, YG and HYBE) responsible for managing the artists who would come to dominate the pop culture landscape over the next two decades. Currently, she is director of the music business for Studio LuluLala (SLL), a leading producer and distributor of Korean dramas or K-dramas, the first of which, Winter Sonata (2002), is credited with spawning Hallyu.

While the love of K-dramas and K-pop was traditionally confined to Asia, it was the rapper Psy who took Hallyu global with his 2012 hit “Gangnam Style,” featuring his iconic “horse dance.” Lee recalls this as a period of rapid change, of constantly creating fun new content, when pop idols were being made, and when the business of peer-to-peer (P2P) sharing of downloadable music-and-video content for playing on MP3 players was taking off and being systemized. “I learned hands-on,” she says.

The industry began to consciously cultivate a fee-paying fan culture, through membership clubs, merchandising and magazines. Taking a leaf out of the Japanese playbook, they created handbooks with clear guidelines for artists to follow during interviews and for managers to know how best to look after their artists. Hallyu became a slick operation.

The revolution will be televised

Although Korea’s world domination seems to have happened overnight, Lee says it’s actually the result of several serendipitous factors that evolved over the past 20 years — namely, the ubiquity of digital and internet tools, combined with the advent of YouTube, music streaming platforms like Spotify, and over-the-top (OTT) players like Apple, Amazon, Disney+ and Netflix, which has introduced K-dramas to households all over the world. “The revolution in the content distribution network has broken down the barriers to Korean content and helped to globalize it.”

Each channel reinforces the other. YouTube, for instance, not only lets people all over the world listen to music through videos, it also generates advertising income and, by globalizing name recognition, allows the artists to tour overseas. This generates virtuous circles and makes it easier for entertainment executives like Lee to win corporate sponsors and other promotional opportunities.

Whereas, in the past, producers, marketers, A&R reps and managers tended to operate separately, today there is much more coordination between roles and functions, so all teams work together in a much more systematic way. “Given that people start listening to music on their phones,” says Lee, “the way of marketing an album has changed into connecting with fans and building followers.”

Apart from the speed of new technologies and distribution networks, Lee also thinks that “as a culture, we’re really fast. We adapt to changes in the environment very quickly. Even in the restaurant trade, you usually have to change the business every two years, because Korean tastes change so quickly. Because we have this pioneering mindset — we have to keep trying new things — this might explain why Korea has sought to expand out into the world rather than just focus on the local market.”

“I think Korea makes content that people around the world can connect to, with universal emotional themes,” she adds. So, K-pop blends familiar musical genres like hip-hop, rock, R&B, jazz and disco, with inclusive lyrics about love and acceptance. Even with the darker K-content — such as the 2020 Oscar-winning best picture Parasite or the 2021 Netflix series Squid Game — the themes of wealth inequality, or the conflict between individual choice and community, resonate with global audiences struggling with the same issues.

A force for good

The K prefix is increasingly being applied to everything, not just pop and drama but beauty products and food (from pickled kimchi to bibimbap rice bowls, 2021 was considered the year when Korean food went mainstream, with nearly 1 in 3 people surveyed worldwide saying Korean food was now very popular in their country).

“Some analysts say the spread of Hallyu can be a driving force for increasing the share of our export market, due to an indirect advertising effect,” says Lee.

According to Foreign Affairs, Korean cultural exports (including computer games, concerts and cosmetics) accounted for $12.3 billion in 2019 (up from $189 million in 1998). BTS alone has been said to have generated $3.5 billion a year in economic activity, with an estimated 7% of all tourists saying they went to South Korea just because of that one group.

In addition to the positive spillover effects that soft power can bring to the bottom line, K-culture is making a positive social impact, too. BTS, for example, has mobilized its fiercely loyal fanbase — known as the ARMY — to encourage everything from vaccination to voting. BTS fans in the Philippines have raised funds for Palestinian children’s relief, while others have supported the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S. The ARMY has become a registered charity, leveraging its strong global network for the purpose of being a force for good in the world.

“K-pop fans are actively working together on social, political and environmental causes. In some cases, the power of these fans is bigger than any official political or social power,” says Lee.

While this may represent a welcome shift from cold, aloof stars who try to keep their distance from stalkerish fans, Lee says that it does require careful management to ensure that such fandom stays on the right track, otherwise such power could be exploited for less charitable ends.

Lee acknowledges some of the less savory stories that have emerged from the industry, with some K-pop stars accused of abusing vulnerable fans or having mental-health challenges because of the intense pressures they’re under to appear perfect all the time. “It can become a real psychological burden to constantly satisfy your global fans,” she says. “As this industry expands so rapidly, we need to think more about such issues and invest in developing more institutional devices, so we can take the necessary action.”

Can the model be replicated?

Hallyu did not just happen by chance. Achieving such results on a global scale takes a concerted effort by many different actors. “The sweat of many K-pop artists, investors and production companies has paid off and it will take continued effort to sustain and grow, especially in an increasingly capital-intensive global market,” says Lee. “And as the industry gets larger, inevitably more effort and institutional mechanisms will be required.”

But Lee admits that sheer effort alone is no guarantee of success: “I don’t think anyone can intentionally create a culture that works well. Culture, by nature, belongs to the public. And at the end of the day, the public decides.”

That said, Lee speculates that with advanced big data systems and custom platform strategies, there may be scope for reading trends in real time and simultaneously customizing content according to various demands. In this way, “Hallyu culture could continuously grow further by design.”

It is hoped that BTS will be able to continue their winning streak, even though one member of the group, Jin, has already had to take time off for mandatory military service, and soon the other members will have to follow suit.

Lee Areum: “K-culture has not peaked. I believe we can achieve even greater success.”

Lee Areum: “K-culture has not peaked. I believe we can achieve even greater success.”

Lee is optimistic about the future of other K-culture content because it is ultimately about intellectual property (IP). “IP is property, and it’s a weapon that can be permanently deployed,” she says, explaining how the IP owner can diversify into different content categories using the same successful brand label, like Disney does. “If we continue to invest in Korean content, and keep expanding the business lines, in the end, I think IP will be the winner.”

As for herself, Lee, who got into this business because she liked marketing and promoting content, is now more interested in the distribution and investment side. “I’ve moved to where I’m researching the IP, like I just mentioned, so that I can expand in the direction of platform broadcasting.”

“The current K-culture has not peaked,” she insists, noting that Netflix has committed to producing even more big-budget K-dramas. “K-culture will continue its golden age and I believe we can achieve even greater success.”

As BTS might say: Dynamite!

A version of this article is published in IESE Business School Insight 163 (Jan.-April 2023).