IESE Insight

3 steps to the right investment mix

Asset allocation is one of the most important decisions facing investors. Find the appropriate mix of stocks, bonds and other assets.

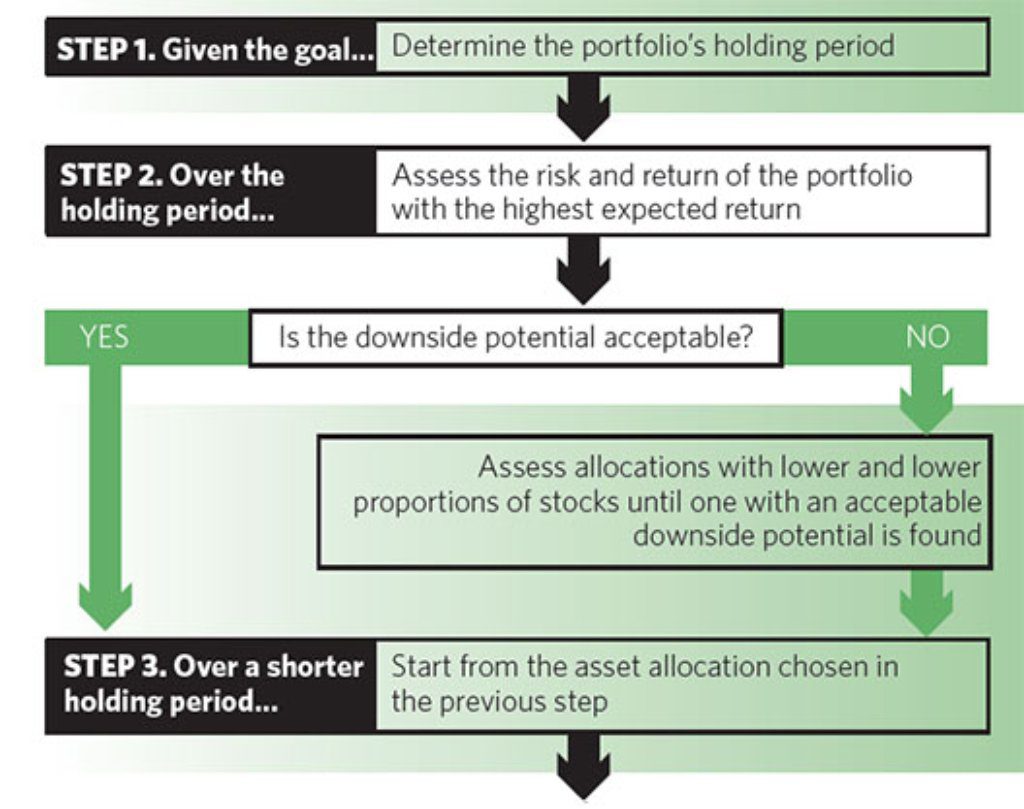

Looking to build an investment portfolio? Professor Javier Estrada offers an approach to asset allocation broken down into just three steps, as explained in his article for the Journal of Asset Management.

"Determining the optimal combination of stocks, bonds, and other assets for any individual is a mix of art and science," Estrada notes. And yet it's also widely regarded as one of the most important decisions investors make. Estrada's proposal is an approach to asset allocation that's relatively simple, yet sound.

He calls his three-step approach to selecting the right mix of stocks, bonds and other asset classes "GHAUS" — a label capturing the five variables considered:

- the Goal,

- Holding period,

- Ability to tolerate losses,

- Upside and downside potential, and

- Shorter holding periods, to be explained below.

Ready, set, go (and repeat as necessary)

The three steps for investors are as follows:

1. First, decide on the portfolio's goal and its holding period. I.e., is this for retirement? Is it intended to help pay for the twins' college educations? Or do you want to see returns in just a year or so?

2. Next, evaluate the risk-return trade-offs for a set of asset allocations. This second step is the main focus of the GHAUS approach, Estrada explains. Looking at U.S. stock and bond returns over a span of 50 years, divided into distinct time periods, Estrada offers numbers to illustrate upside and downside potential. These hypothetical gains and losses, and the chances of experiencing them based on historical data, are key for risk assessment.

For example, by investing $100,000 in only stocks and holding on for five years, an investor had an 11.1 percent chance of losing an average of $8,326, per Estrada's calculations of historic data. (See Methodology, Very Briefly). Increasing the percentage of bonds in this hypothetical portfolio lowers the downside potential (while limiting the upside potential). This exercise of walking through possible outcomes, based on historical data, can help an investor find a sweet spot, where both positive and negative case scenarios are acceptable.

"It is important to stress that the focus of the analysis should be on the probability and magnitude of potential losses, and not on the expected return, of the feasible set of allocations," explains Estrada. That is because, "an investor is far more likely to bail out of a portfolio if the losses are more frequent or higher than he is able to bear than if the return is not as high as he would like it to be." On a related note, previous research has shown that individuals weigh losses more heavily than gains of equal magnitude.

3. Which leads us to the last step. The third and final exercise is to repeat step two, but for shorter holding periods. This is to recognize that an investor saving for retirement, an event that may be decades away, is affected by short-term swings. For example, Estrada calculates that after just one year, a $100,000 investment allocated as 60-40 for stocks and bonds, respectively, was worth less than $93,000 for 17.1 percent of portfolios. This final step (repeated, as necessary) should allow an investor to find a truly appropriate asset allocation. With this stress test, an investor should be ready to hold on for the ride.

Estrada recommends the GHAUS approach because it is simple and intuitive. He also notes that "it captures downside potential through the probability and magnitude of expected losses, which to most investors are more meaningful than volatility as a measure of risk."

Methodology, very briefly

To provide a concrete example of upside and downside scenarios for portfolios with stocks and bonds, Estrada turns to 50 years of data. Stocks are represented by the S&P 500 and bonds by 1-year US Treasury Bills. Monthly, nominal returns for 21 asset-allocation scenarios over three holding periods are calculated for the article.