IESE Insight

Innovative spirit: lessons in leadership from the Sagrada Familia

The Sagrada Familia by the architect Antoni Gaudí is proof of how to turn vision into reality. By taking a cue from Gaudí, executives may be inspired to realize their own visions in ways they never thought possible before.

"The tree outside my window is a great teacher," the architect Antoni Gaudí once said. Indeed, stepping into the temple of the Sagrada Familia, his most famous and perennially unfinished work, is like stepping into a forest. Pillars rise like trees, separating into overlapping branches that hold up the ceiling. It's a revolutionary structure in architecture, and yet the structures can be found in nature.

Nature is everywhere in the Sagrada Familia, both in decorative elements — sculpted lizards, birds and ivy on the façade, turtles supporting columns, clusters of fruit atop towers — and, crucially, in its structure. There is the internal forest, but also the spiral staircases that echo the form of mollusks and innovative elements such as catenary arches. For Gaudí, the new was to be found in the timeless and in our everyday surroundings that we see so often we sometimes fail to see them at all.

Nearly 140 years and counting in the making, the Sagrada Familia demonstrates how visionary leadership can prioritize the truly important over the distracting noise of short-term results and ego. By taking a cue from Gaudí and seeking the extraordinary in the ordinary, executives may be inspired in ways they never thought possible before.

An inspiring vision

Gaudí was a man with a vision, and one who understood that the vision must be clearly communicated to be effective.

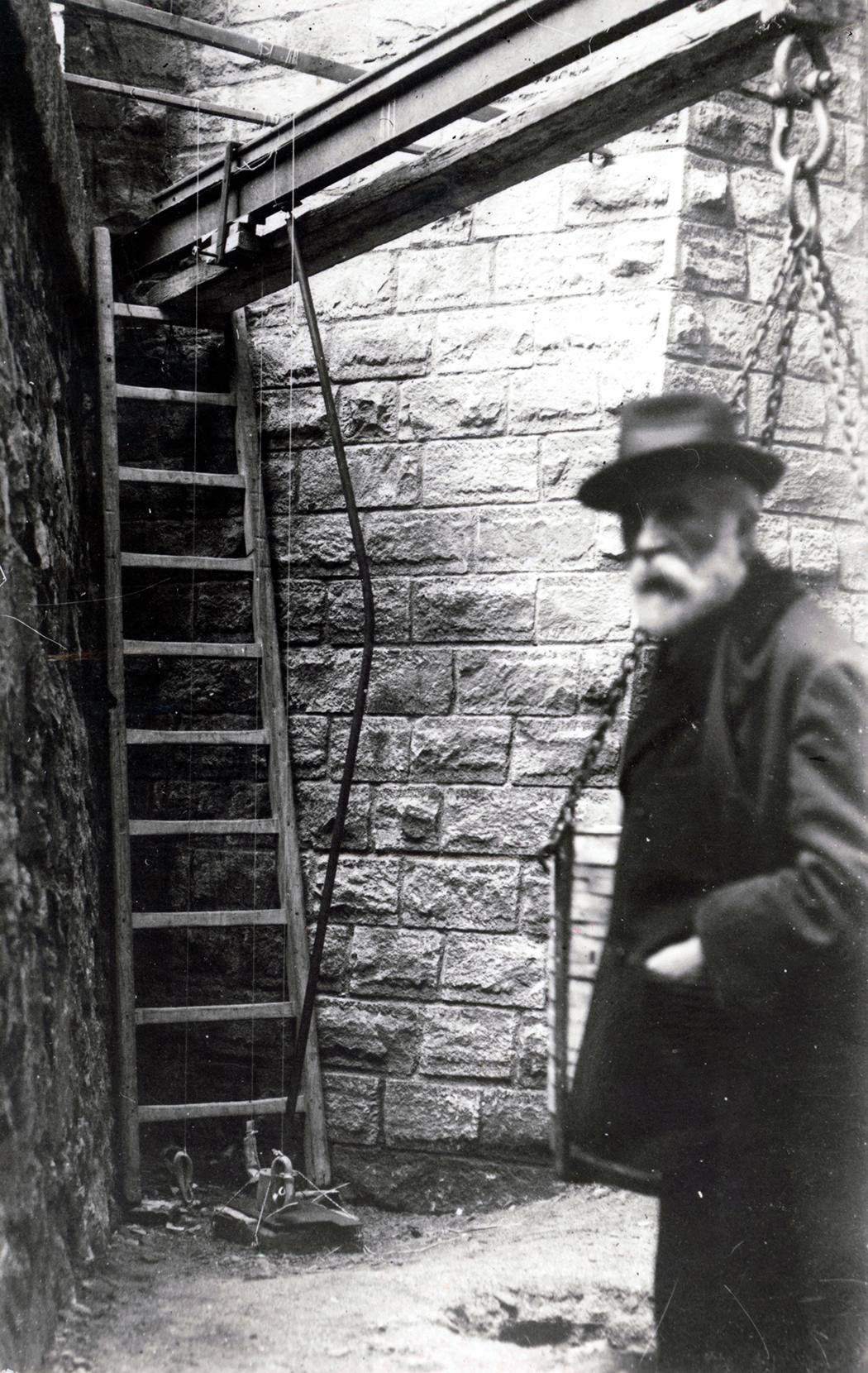

A master craftsman who worked among master craftsmen, Gaudí created drawings and extensive plaster models of his planned church, and then allowed his colleagues — ironworkers, stoneworkers, ceramicists, many of them lifelong collaborators — to work out the details without constant oversight.

Another effect of this clearly communicated vision was that when many of these drawings and models were lost in a fire after the architect's death, those assistants and collaborators were able to recall much of the plan and communicate it to the next generation of architects.

And what was this vision? The church is immense, with 18 spires, some of them colorfully enameled. It's also richly detailed: façades crammed with natural and religious motifs, spiral staircases, a forest-like interior and stained glass refracting different primary colors onto the cool white walls as the day progresses. With such an awesome vision, Gaudí wanted to both dazzle and humble the visitor, for them to "see what is there and what is not there."

The inescapable fact of money

The practicalities of turning such a vision into reality were daunting. If the master craftsman was, on the one hand, a dreamer, he was also, on the other, a realist.

The Sagrada Familia required vast sums of money to build, much greater than any of his previously funded projects. Moreover, as an expiatory temple, it would need to rely on individual alms rather than institutional grants for funding. It would also take a great deal more time, measured not just in years but generations.

Gaudí accepted this reality of innovation: just having a great idea wasn't enough; he also needed to convince others of its greatness and inspire them to contribute, both now and long into the future. He was a tireless fundraiser, even pouring his own earnings into realizing his dream. Yet the lion's share of the funds came from thousands of individual donations, truly making it a work by and for the masses who had been moved to buy into Gaudí's vision.

Building a legacy

Work on the Sagrada Familia was done in stops and starts. Gaudí didn't see this as a bad thing. Indeed, "it is necessary to alternate between reflection and action, which complete and moderate each other," he said.

Slow periods in the building were used to take stock, to dream and design new solutions, and for Gaudí to develop his skills in new directions, as he worked on many other projects at the same time. Later, from 1914 until his death, he devoted his time exclusively to building the Sagrada Familia.

For Gaudí, it was clear to him that the Sagrada Familia was not a moneymaker but a legacy project, a work he would never live to see realized. When he died in 1926, hit by a tram while walking to Mass, he had built the Nativity Façade and erected four towers, only one of which was complete.

After dedicating a lifetime to a project, a lesser person might feel frustrated not to see its completion. Yet Gaudí's big-picture vision accepted, even welcomed, that possibility. "There is no reason to regret that I cannot finish the church," he said. "I will grow old and pass away...but its life must depend on the generations it is handed down to." Words to live by, in any profession.

IESE has done a case study on Gaudí and leads tours of the Sagrada Familia, followed by a discussion, during Executive Education programs at IESE Barcelona.

Antoni Gaudí: the focus was on the project, not himself

Ask yourself: What kind of leader are you? What kind of leader do you want to become?

A version of this article is published in IESE Business School Insight magazine #154.

If you liked this article, you may also enjoy reading: The cornerstones for building a better business world