IESE Insight

Globesity: Connecting globalization and obesity

Thanks to globalization, the world may seem smaller, but the people in it are actually getting larger. Obesity is a pandemic, and the social aspects of globalization may be to blame, according to a paper by Joan Costa-Font and Núria Mas.

The balance has tipped. For the first time in human history, there are more overweight people than underweight people.

The dimensions of this shift are alarming. The average body mass index (BMI) since World War II has accelerated at an unprecedented rate. Currently, an estimated 1.5 billion adults are considered overweight and 500 million are considered obese.

The World Health Organization warns that being overweight or obese is the fifth highest risk factor for mortality. Obesity is also a major cause of rising healthcare prices in advanced economies.

Professors Joan Costa-Font of the London School of Economics and Núria Mas of IESE look for the root cause of the obesity problem in their article titled "'Globesity'? The Effects of Globalization on Obesity and Caloric Intake." They are the first to empirically analyze the correlation between obesity and globalization. Digging down into their data, they find that the social aspects of globalization — such as changes in media consumption — are especially significant.

Here's a brief look at what has been observed and what remains to be discovered about the correlation between increasing globalization and increasing girth.

Why is the problem growing larger?

Some researchers have wondered if it's our genes making us fatter. Yet genetic changes can take generations to unfold while obesity rates have nearly doubled since 1980.

What about food prices and availability? It's true that diets today tend to contain more fat, sugar and animal products. Moreover, one study estimates that a 10 percent increase in the price of fruits and vegetables increased BMI by 0.7 percent in U.S. children.

What about our increasingly sedentary urban lives? This could explain the obesity phenomenon for some countries, but not for others.

The co-authors note that these factors, while significant, simply do not add up to explain the enormity of our obesity problem.

The breakthrough: Linking globalization to obesity

There's something else that has nearly doubled in the past 40 years: the level of globalization in most countries. Costa-Font and Mas had a eureka moment when they linked globalization indices with the obesity rates of 26 countries.

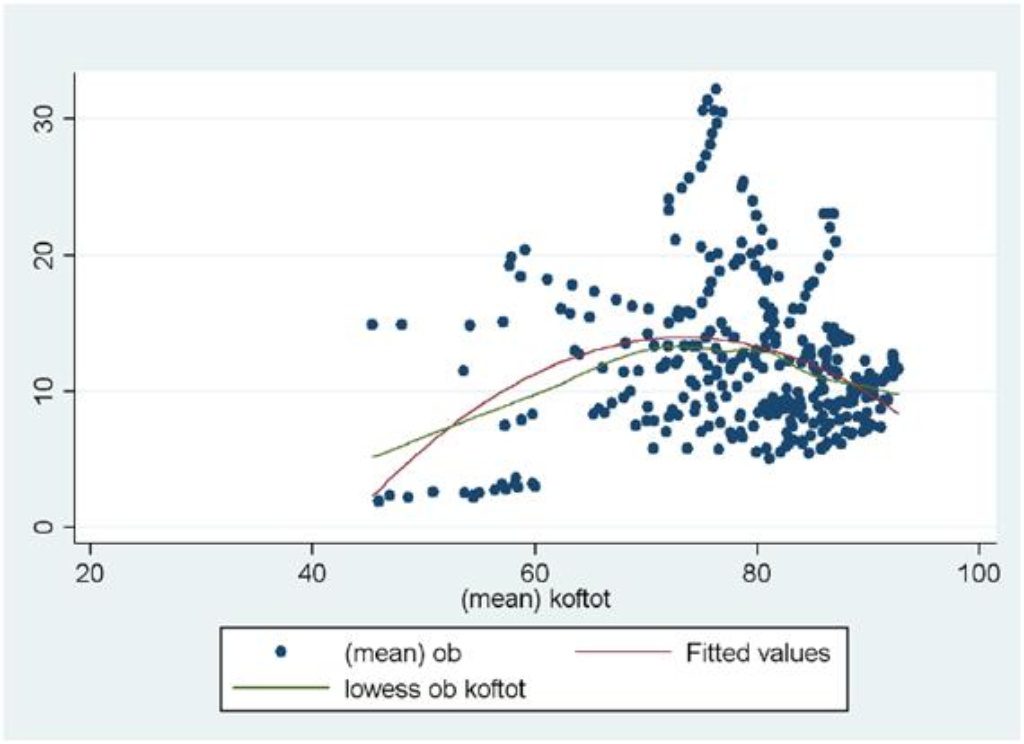

In the graph below, the percentage of the adult population considered obese (with a BMI over 30) is on the vertical axis and globalization (measured via the KOF index) is on the horizontal axis.

Variation of obesity rates and globalization

When countries climb the ladder of globalization, their populations get fatter. The average obesity rate in the countries measured was 12 percent. And for each statistically significant step up in globalization, the co-authors saw a pronounced rise of 20 percent in the proportion of obese population, although the rates appear to level off after a higher level of globalization is reached.

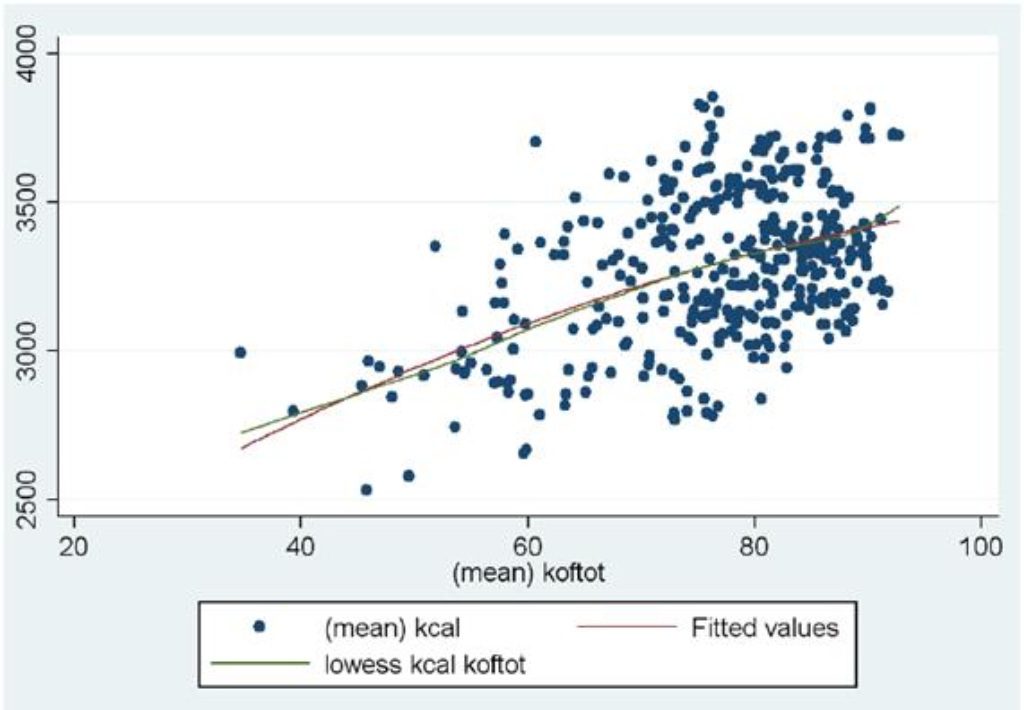

In the next graph, the number of calories consumed each day is plotted against globalization levels.

As globalization kicks in, we consume a lot more calories. And this correlation does not level off. In fact, for every extra globalization point, we eat an extra 74.8 calories per day — the equivalent of a small piece of fruit.

But it isn't fruit we're reaching for. For every extra point of globalization, the population is eating an extra 17 grams of fat. Over time, the pattern is clear. The average U.S. citizen, for example, increased her daily fat intake from 138 grams to 163 grams over the past 15 years. That is more than one extra gram of fat for every year.

Kinds of globalization

So why is globalization making us fat? To find clues, Costa-Font and Mas distinguish between the various international links that make up what we know as globalization.

The KOF and other indices break globalization down into three categories:

- Economic dimensions (trade flows, etc.).

- Political dimensions (treaties, foreign embassies, etc.).

- Social dimensions (the spread of ideas, information, images and people).

In addition, the co-authors introduce an extensive list of control variables to better understand how globalization might affect obesity. These control variables include changes in GDP, income inequality levels, food prices, urbanization, education levels and population growth.

As a result, the co-authors found the economic dimensions easy to explain. For example, when food prices climb, we often end up eating cheaper things — often junk food.

As Mas put it: "When you have all the obvious things under control, you're left with the hardest, biggest part of the mystery: the social dimension. It accounts for a very significant percentage of all the results.... We know it's key, but we just don't understand exactly why."

Stopping globesity at its source

Knowing what is making us fatter on a global scale is a key first step to finding remedies. The social dimension of the globesity problem merits further research. Which are the most important social factors? Does watching blockbusters make you eat more than, say, classic French cinema? How does being close to the global mainstream affect obesity? And what might the omnipresence of mobile phones be doing to our waistlines?

In the meantime, opportunities abound in many industries to promote prevention and healthy habits, Mas notes. Healthy interventions are key, as the globalization trend continues. Examples include more nutritious foods, new designs in sports clothes and emerging initiatives to bring together big data, knowledge and technology to promote healthy lifestyles. Mas says that it's time to start thinking about health beyond traditional health care.

Methodology, very briefly

The authors studied a panel of 26 countries over the years 1989-2005, the period when globalization took off most dramatically. The data contains the maximum number of countries whose data could be collected at the time of analysis, over the longest period. A number of controls were included to take into account such other factors as urbanization, lower food prices and women's increased participation in the labor market.