IESE Insight

Globalization in troubled times

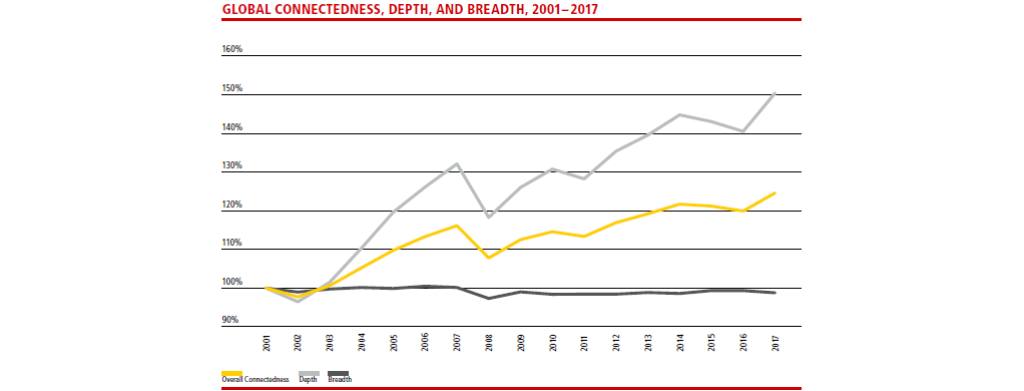

For years, the DHL Global Connectedness Index has been making the case that the world is not as globalized as we think. This is still true; yet surprisingly, in the age of Trump and Brexit, globalization has actually reached a new high.

In 2016, the United Kingdom voted for Brexit and the United States elected Donald Trump, spelling, for many analysts, a major setback to globalization.

However, the latest DHL Global Connectedness Index — the first comprehensive globalization study to contain data from 2017 — is quick to put this idea to rest. Looking at global connectedness on a worldwide level, by region, and for 169 countries with historical coverage back to 2001, the data show that globalization actually increased to a record high in 2017.

Source: DHL Global Connectedness Index 2018

For the first time since 2007, international trade, capital, information, and people flows all intensified significantly, helped by a strong economy and not (yet) affected by policy changes implemented in 2018.

Even so, Steven A. Altman, Pankaj Ghemawat and Phillip Bastian remind us that the world is still much less globalized than we think. Only about 20 percent of economic output is exported. Foreign direct investment equals 7 percent of global gross fixed capital formation. Just 3 percent of people live outside of the country where they were born. If those numbers strike you as smaller than expected, you're not alone. Most people think the world is more globalized than it is, and this is an important driver of fears about globalization.

Other key takeaways

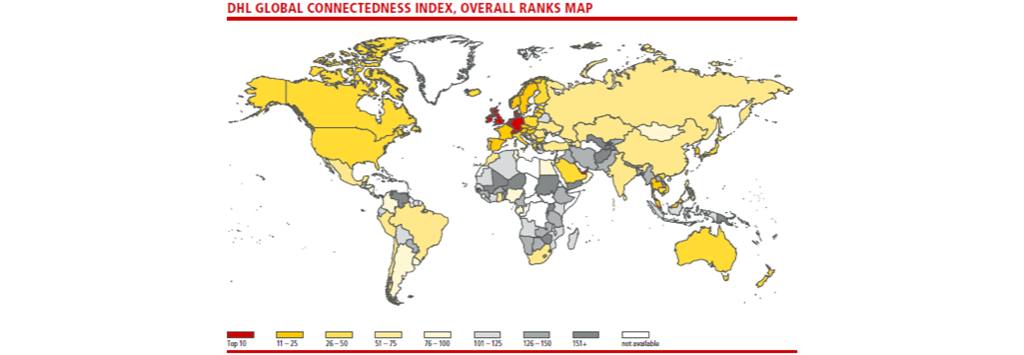

The world's most globally connected country? Neither the United States nor China, which didn't even make the top 10, but the Netherlands. Singapore came second, followed by Switzerland, Belgium, the United Arab Emirates, Ireland, Luxembourg, Denmark, the United Kingdom and Germany. Europe was the most connected world region, contributing eight of the top 10 countries and also topping the ranking for trade and people flows. Meanwhile, North America, the second most connected region, led in capital and information flows.

Source: DHL Global Connectedness Index 2018

Advanced economies in general had much higher average levels of connectedness than emerging economies. Not all the action is in Europe and North America, however. Not only did Singapore rank second overall, it was also first in terms of the size of international, relative to domestic, activity. Lower income, developing countries where international flows exceed expectations are Cambodia, Malaysia, Mozambique and Vietnam. The heightened performance of so many Southeast Asian economies is proof of the globalizing impact of regional supply chains.

Even so, globalization often takes different forms in advanced and emerging economies. International trade is a feature of both, but advanced economies are three times as deeply integrated into international capital flows, five times for people flows, and nine times for information flows. Meanwhile, the progress of emerging economies catching up on global connectedness has stalled since the 2008 global financial crisis.

Where to from here?

The globalization debate is characterized by strong feelings on all sides, as well as strong misconceptions. The authors highlight, for instance, that half of all international flows are between countries and their top three origins and destinations — which highlights how much distance and cross-country differences still constrain international business, despite the latest advances in transportation and telecommunications.

Meanwhile, many of the protectionist policies promised in 2016 came into effect in 2018, while 2019 heralds Brexit, deal or no deal. Globalization may indeed be under threat, though the authors caution that declaring it dead is as much an exaggeration as declaring it inviolable 10 years ago was.

There are many potential repercussions to how globalized the world is seen to be, compared to how globalized it really is. The report highlights the case of immigration, a major policy issue and talking point in both the Brexit and Trump campaigns. The authors write: "On both sides of the Atlantic, people believe there are more than twice as many immigrants as there really are, and when they are told the correct proportions of immigrants in their countries' populations, the share of survey respondents viewing immigration as a problem declines." There is a clear need for debates about global connectedness to feature facts, not fictions.

Policymakers are key to how globalization will continue to develop, or not. The index demonstrates the positive effects on growth of greater connectedness, and the good news is that, with limited globalization worldwide, even the most connected economies have plenty of room to deepen or broaden their international flows.