IESE Insight

The nuts and bolts of fast fashion: the secrets behind Zara and H&M’s winning operations formula

What’s the secret to Zara’s success? The operational pillars of the fast-fashion business model are explained. Where else might they apply?

How do retail success stories like Zara and H&M manage to constantly refresh their selections and keep prices low?

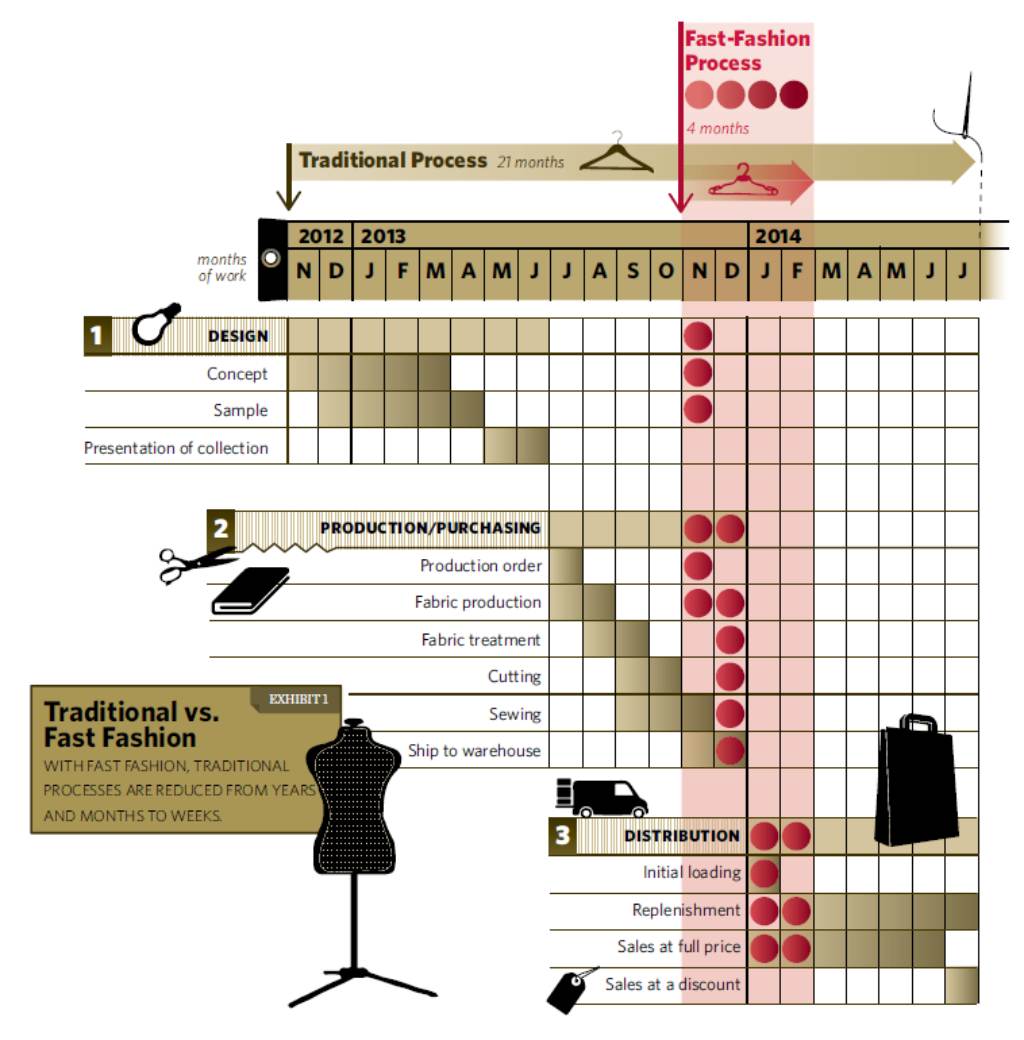

The answer lies in the fast-fashion business model — a way of selling clothes that takes advantage of Quick Response (QR) production and dynamic assortment planning, shrinking the time it takes to go from design to distribution, and back again.

Felipe Caro, professor at UCLA Anderson School of Management, and Victor Martinez de Albeniz, professor at IESE, provide an illuminating look at the business model from an operations standpoint. In their chapter for the textbook Retail Supply Chain Management, they explain the nuts and bolts of the business model and describe untapped areas for future research.

Why is fast fashion worthy of close study? For one thing, it is growing faster than the traditional apparel market. Just think: The two largest clothing retail companies in the world — Spain’s Inditex (owner of Zara) and Sweden’s Hennes & Mauritz (owner of H&M) — rely on the fast-fashion business model.

Also, the fast-fashion business model may enter into food, music and other areas where trends matter or consumer fatigue is an issue.

What is fast fashion?

First, the professors spend some time defining their terms. After all, the fast-fashion business model can only be understood in terms of fast fashion itself.

Fast fashion is not Chanel, Prada or similar high-priced luxury brands. Fast fashion is, by definition, much more affordable for frequent shoppers. Also, fast fashion is not Gap, Uniqlo or similar suppliers of affordable staple items. T-shirts and jeans may stay on the shelves season after season, while fast fashion offerings ride trends, like surfers catching waves.

So, fast fashion is always about fashionable designs at affordable prices. Its value proposition is based on both product freshness and bargain prices.

In a competitive fast-fashion landscape, optimizing operations to provide frequent assortment changes at low prices is key. To that end, fast fashion is supported by two operational pillars: Quick Response (QR) production and dynamic assortment planning.

Quick Response (QR) production

Quick Response (QR) was originally developed in the textile and apparel industry as a set of standards for information exchange and supply chain management that shortened lead times and increased supply chain efficiency. Over time, the use of the term QR has evolved to indicate a simple concept: postpone all risky production decisions — e.g., commitments to purchases that may not be needed in case of low sales — until there is enough evidence that the market demand is there. QR thus allows a reduction of excess inventory, although per-unit costs related to manufacturing and shipment may increase.

Information is a key driver of QR decisions. Demand forecasting in fashion works best when early sales data are used to predict subsequent sales more reliably. New designs are quickly produced in small batches to collect data early and often.

Along with information, production factors are fundamental for QR. Eschewing seasonal collections and working item by item allow fast-fashion companies to accelerate lead times across the board. Importantly, the seasonal bottlenecks of traditional production processes are avoided.

In addition, production schedules may be sped up through the use of nearshore suppliers, located close to the target market. For U.S. companies, nearshore suppliers may be located in Mexico and Central America. For European companies, factories may be located in Bulgaria, Morocco, Portugal, Romania or Turkey. Fast-fashion companies try to anticipate how much of what goes where at the last minute, to send inventory where it’s needed most.

Dynamic assortment planning

The second operational pillar for fast fashion is the use of frequent assortment changes throughout the season. Store offerings are updated as often as daily — not just a few times a year, as in the traditional model. These constant changes have been proven to increase store traffic.

To optimize the timing of new products into the mix, dynamic assortment planning is required. The co-authors note that demand for any new product will typically decrease over time as newer products tend to get better displays and generate more interest, all else remaining equal.

The co-authors continue to work on formulas for finding the best time to introduce a new product and then the next one, typically just as soon as any drop-off in demand is detected.

Note that frequent assortment changes work when apparel makers control their own stores. In the wholesale business model, pre-orders are key, so the timing is different.

Constantly changing inventory in stores works well in combination with QR production, controlling inventory and keeping margins healthy. Fast fashion becomes a truly compelling business model when solidly resting on both of these pillars.

Sustainability as a fundamental concern

Is fast fashion sustainable over the long term? What might its global impact be?

Critics of fast fashion tend to point to three fundamental challenges: waste, working conditions and local consequences for a global supply chain. In their chapter overview, Caro and Martinez de Albeniz note that companies are starting to respond to these challenges.

- Waste. In response to outcries over waste, H&M, for one, is offering a recycling program. Old clothes brought in by customers then reduce the waste.

- Worker conditions. Offshoring based on economic motives and considerations may ignore ethical elements, like safety conditions and living wages. Accords and codes of conduct are being introduced to help regulate the industry and protect vulnerable workers. For example, since the Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013, more than 190 brands and retailers have signed the Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry in Bangladesh to improve conditions there. More safety standards and other worker protections are needed.

- Global industry, local consequences. In the face of global demand, fast-fashion companies should remain mindful of the fact that their sourcing and production strategies may end up shaping a particular region’s capabilities. To this end, Inditex’s clusters program brings together local unions, NGOs, trade associations, governments, international purchasers and members of civil society to promote a sustainable environment in the regions where it operates. Inditex has clusters in Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Cambodia, China, India, Morocco, Pakistan, Portugal, Spain, Turkey and Vietnam, representing the vast majority of the company’s production locations.

In a more recent interview for IESE Business School Insight magazine, Oscar Garcia Maceiras, who became CEO of Inditex in November 2021, said: “We want to lead the transformation of the industry through responsible management in collaboration with a good number of organizations, including IndustriALL, the international trade union federation with which we have a pioneering Global Framework Agreement to put the worker at the center, promote continuous social dialogue and ensure optimal labor standards.”

What next for the fast model?

For future research opportunities, the co-authors look to other industries where products rotate frequently and consumers are searching for novelty. Food, consumer electronics, books, music and movies are a few areas mentioned.

For example, dynamic assortment planning can help music executives decide when to release new songs for radio play. By detecting immediately when demand starts to wane, new releases could be better timed to engage new customers.

Could fast operational strategies change your industry next?

MORE ON THIS SUBJECT: How fast fashion works: can it work for you, too?

READ ALSO: Economist Rita Babihuga-Nsanze discusses Africa’s vast potential: “Because African countries cannot compete in the way China did initially, on wages, they’re trying to differentiate themselves on the sustainability front. As Western consumers get increasingly fed up with fast fashion, they’re looking for more sustainable ways of consuming textiles: this becomes an entry point for some African countries.”