IESE Insight

Boosting firm performance with the business model effect

Does a company's business model affect its performance? Govert Vroom's research says yes — it's just as important as the choice of industry in determining a firm's success.

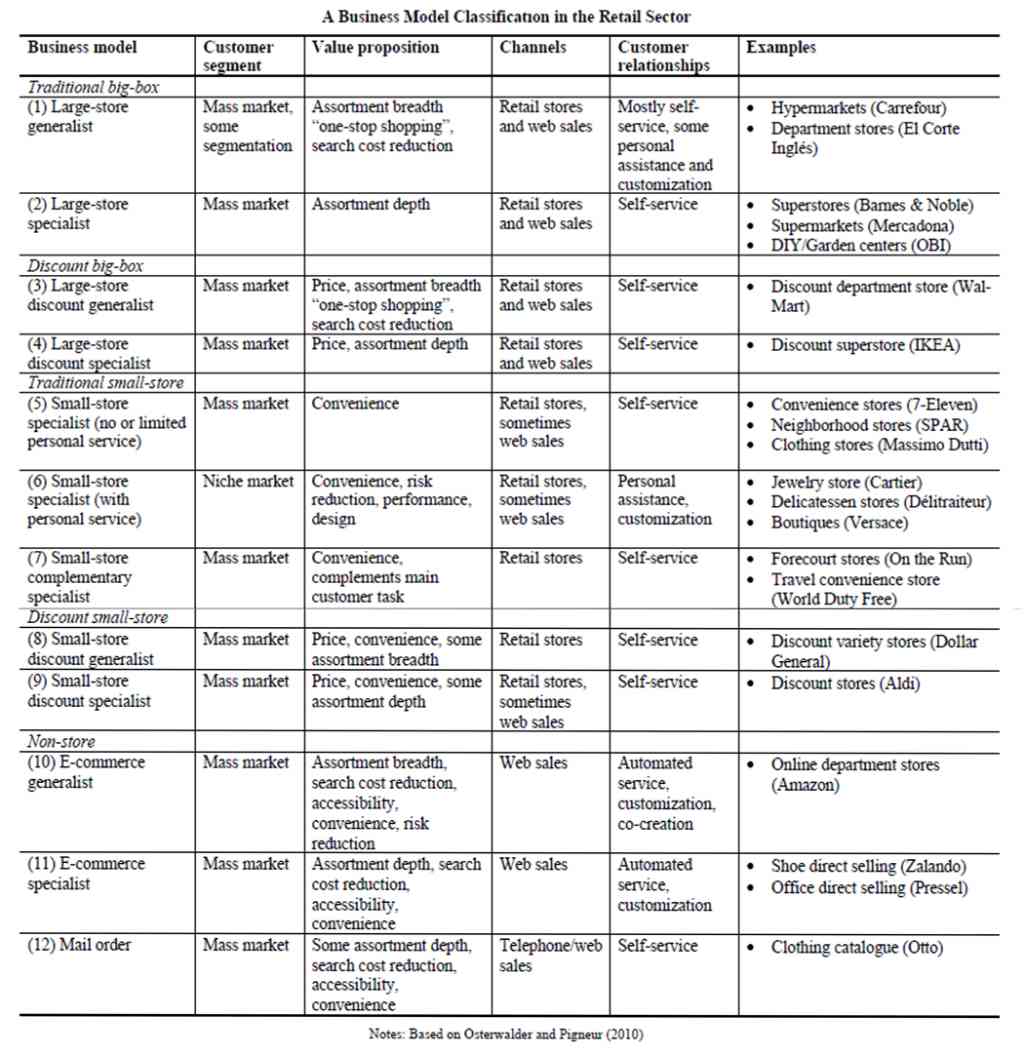

Carrefour offers a large assortment of products in one place, with high fixed costs but the advantages of economy of scale. Barnes & Noble works in a similar way, but provides a "deep" assortment of products, rather than a broad one. Large-store discount generalists (like Walmart) and large-store discount specialists (like Ikea) also differ from one another, and from other large stores, in their value propositions, cost structures and other elements. The differences described here are all differences in business model.

Debate continues in management literature on whether, or how much, the business model matters, in comparison with other factors such as product, industry or network.

IESE's Govert Vroom, working with Timo Sohl and Markus A. Fitza, decided to put business models to the test. They studied 917 retail companies, from Aldi to Ikea, to see how firm performance varied according to business model. They conducted interviews and analyzed data, covering 29 countries and 23 industries over 11 years, from 2005 to 2016, comparing business model effects with other factors like business unit idiosyncrasies, industry, country, corporate parent and the general economic conditions at the time.

The results were decisive. The business model had a significant effect on company success. It accounted for 5.1 percent of a firm's return on assets (ROA), on average. To put this into perspective, that means the choice of business model (i.e., what firms using the same model had in common) is about as important a factor as industry, although it is less important than some other factors — namely, the idiosyncratic resources and capabilities of the individual business units (called "the business unit effect" in the study). Furthermore, distinct business models also contribute to differences in market share — and those differences hold up independent of where a firm operates, in terms of industry and in terms of geography.

A matter of experience

So, business model types are powerful contributors to firm performance. But they don't affect all companies equally.

Vroom and his co-authors wanted to go deeper, to understand which companies benefit most from operating a defined business model type, versus allowing a unique, company-specific way of doing business to evolve. Think Amazon, whose unique resources and capabilities have led to them warping their business model into something quite customized.

As in many other areas of life, it turns out you need to know the rules in order to break them. Concretely, business model type mattered more to firms with less experience, while made-to-measure models worked well for those with more experience. With experience, how you operate the business model becomes more important than which model you choose.

For managers, understanding not only different business models, but when to adapt these and when it just doesn't matter as much, can be key to boosting firm performance.

One dozen business models

Conducting an in-depth study of business models required a classification system. Vroom and his co-authors reviewed past research and interviewed retail and wholesale executives to best categorize dominant business models in the sector.

Business models describe how a company does business — the way all of their activities interact to create and deliver value. Although business models may be adapted to fit specific firms, they tend to follow certain patterns.

In the retail sector, firms are often divided into four broad business model archetypes: (1) small-store, (2) large-store, (3) discount store and (4) non-store (like mail-order and e-commerce). These broad classifications are useful, and often make sense to managers. For example, one convenience store executive told the researchers about his company's difficulty in adding a large, "big-box" retail model to its existing small-store business model, as the different ways of working "required very different skills." But a more nuanced sense of business models is needed to get a full sense of the distinctions between them — and how these distinctions affect performance.

So, the authors turned to "the business model canvas," a tool originally designed by Alexander Osterwalder for mapping and understanding business models across nine areas: customer segments, customer relationships, value propositions, channels, revenue streams, key activities, key resources, key partnerships and cost structures. In total, they identified 12 distinct retail business model types, encompassing both large and small retail stores, specialized and non-specialized, in addition to e-commerce. (See table below.)

The authors measured how much the business model (as well as other factors like country, industry, corporate parent, and idiosyncrasies of the business unit) contributed to the ROA of these companies. They then compared the impact on experienced and inexperienced firms, showing the importance of isolated "business model effects" at different moments in the company.

The best decision is an informed decision, and by getting a clear picture of how various business elements interrelate to produce value, managers can choose the most appropriate model based on their company's experience and needs.